Exile on Stanley Street: new history retraces 170 years of the South Australian School of Art

A new and forensic history of the South Australian School of Art picks through the entrails of a fluid and very feisty local art scene.

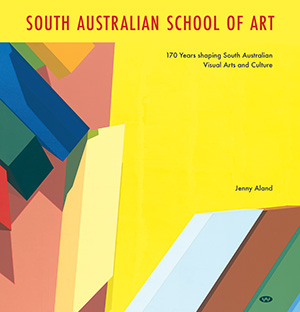

Hard on the heels of Margot Osborne’s broad-sweeping narrative, The Adelaide Art Scene, Becoming Contemporary 1939 – 2000 (Wakefield Press) comes Jenny Aland’s historical tour de force, South Australian School of Art: 170 Years shaping South Australian Visual Art and Culture.

Adelaide now has two pyramids of scholarly research to record Adelaide’s aspirational journey to lay the foundation of an exceptional visual art culture. As with both publications there are multiple entry points depending on the reader’s shared history with some era of the Adelaide art scene or studies. For many who associate with the so-called ‘golden era’ of the School’s residency in Stanley Street, North Adelaide, the book fires up in Chapter 6, ‘Dynamic Adelaide Art Scene Reflects National Artistic Social and Cultural Change’. In the 1960s and into the 1970s the local art scene and with it the Art School, launched into a freewheeling journey of cultural experiment and counter-culture politicisation, fuelled by a sense that change was necessary and countless opportunities beckoned.

In this extensively illustrated and researched narrative the relationship between the School and its relationship with a rejuvenated Contemporary Art Society of SA and the emergence of the Experimental Art Foundation and the Women’s Art Movement, merits its extensive analysis. For a brief period, students, lecturers and academics were offered a glimpse of a post art and even a post art schools future where social relevance and collective action replaced the idea of an art school as an institution intent on training artists for the supply-side aesthetics industry.

At arm’s length Aland’s narrative resembles a seesaw. It builds across the first half of the twentieth century with glimpses of radical change to come, then comes a tipping point as a fresh cohort of lecturers with overseas experience, complemented by emerging local artist/teachers inspired a new generation of fine art students and art educators in training.

You might like

The mix of these two groups in the breeze-block art school build in Stanley Street North Adelaide after banishment from the old Exhibition Building on North Terrace had unforeseen consequences as young people from a wide spectrum of social backgrounds and aspirations, rubbed shoulders. Just out of school kids from Gawler to Brighton and beyond gaped open mouthed at happening events and various bohemian shenanigans.

"Just out of school kids from Gawler to Brighton and beyond gaped open mouthed at happening events and various bohemian shenanigans."

The School became a melting pot of personalities and ideas. As such it fulfilled expectations of the time that an art school should function as a kind of compost heap from which grew exceptional art and artists. This is particularly evident the documentation of a more project-based approach to Common Course delivery implemented in the early 1970s, which in association with expanded media (including photography, installation and performance) introduced a new dynamic which promoted a tutor/student investigative approach. This move was a ‘green light’ to the kind of free-range, cross-media methodologies now commonplace in contemporary art schools.

Subscribe for updates

Aland’s documentation of the School’s peripatetic wanderings across Adelaide, from North Terrace, to Lower North Adelaide, Underdale, then to North Terrace (again) reveals much about the institution’s vulnerability to government policies and the constant struggle for some agency under the stewardship of a succession of governing organisations (SA Education Department, Torrens College of Advanced Education, SA College of Advanced Education and in the 1990s the University of South Australia).

But it also identifies a spirit of resilience and resourcefulness which defined the institution’s ability to move with the times and implement new course structures, create post graduate professional and research pathways and aligned creative disciplines which saw the SA School of Art amalgamated in 2009 with the Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture to become the School of Art, Architecture and Design, then in 2025, incorporated into UniSA Creative. The result of these manoeuvres has meant that the School is now one of the only schools of art in Australia that offers a multidisciplinary approach, giving students one of the widest choices of creative subjects.

The significant contribution of the author’s research is that it identifies key individuals and teams that provided leadership and vision in sometimes challenging circumstances. Space does not allow a listing of those directors, department heads and lecturers who invested their professional lives in The School’s transition from Stanley Street to a re-tasked celery patch (Underdale Campus). Aland titles her chapter on this time as ‘SASA in Exile’. Somehow, as Max Lyle, and others recalled, things muddled through with the Sculpture Department in particular co-opting the bunker-like areas into compliance with flexible pedagogies.

The other major tipping point in this see-sawing journey was the School’s incremental return (as City West) to the city in the 90s, a process effectively completed by 2005 with the Dorrit Black and Kaurna Buildings open for business. Read the fine print to appreciate that it had been an exciting but tough journey for all involved.

From the perspective of the School as an architectural and organisational entity, this publication comprehensively details its journey from the colonial period to the present. The pre- and post-World War One years narrative, particularly of the influence of women including Marie Tuck and Ethel Barringer, and the influence of the Girls Central Art School, deserves close reading.

But the full value of the publication extends to its survey of the wider South Australian cultural and indeed national context to paint a picture of the School as a product of many ideas and factors. Aland’s forensic festooning of the entrails of a very feisty local art scene reveals the fluid nature of the Art Schools relationship with the broader art scene and its communities. In this regard identifying and commenting on the roles played by the commercial gallery sector, artists collectives, art spaces, institutions, and lead agencies, paints a picture of the South Australian art scene and within it, the ebullient SA School of Art, as an artful dodger relying on the collective resources of generations of creative souls to prevail, no matter the odds.

Futurologists predict that art schools must and will change. Perhaps they will become smaller and more specialised. They may cease to exist as physical entities, replaced by globally linked, ‘garage-band’ collectives. Buckle up. It’s going to be an interesting ride.

South Australian School of Art: 170 Years shaping South Australian Visual Art and Culture by Dr Jenny Aland (Wakefield Press) is out now

Want to see more stories from InDaily SA in your Google search results?

- Click here to set InDaily SA as a preferred source.

- Tick the box next to "InDaily SA". That's it.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence