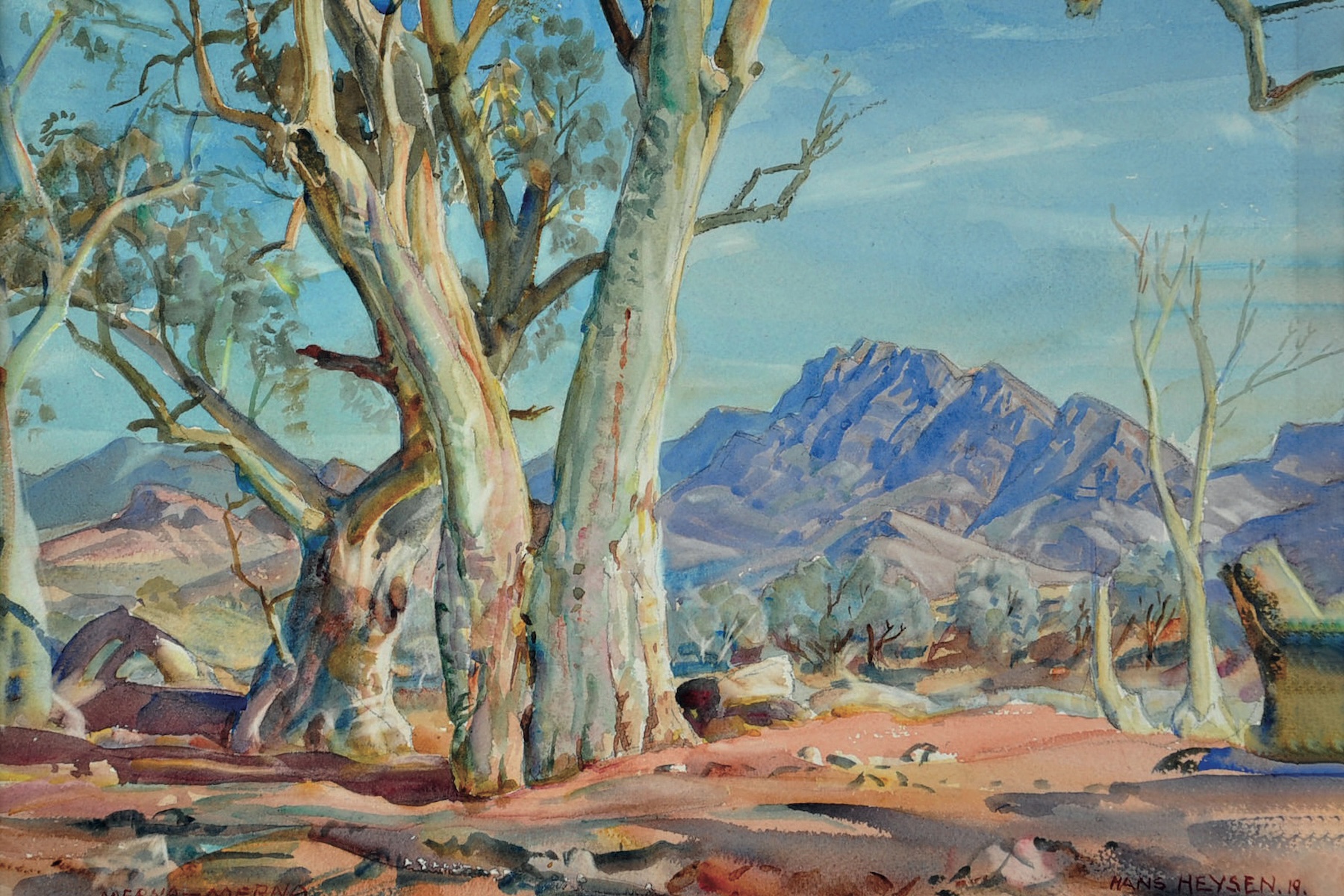

Heysen heads for the hills: private letters reveal artist’s Flinders Ranges fixation

In an extract from her new book, Hans Heysen Was Here, Barbara Cameron-Smith reflects on the legendary artist’s relationship with the Flinders Ranges, captured in years’ worth of letters back home.

Having grown up 1600 kilometres east of the South Australian border, it took many years to discover that Sir Hans Heysen, Australia’s legendary painter of gum trees, also had a thing for high hills.

It wasn’t until planning a swing through the Flinders Ranges in late 2012 / early 2013 that I discovered that two of his best-known landscapes from the Far North – Patawarta: Land of the Oratunga (1929) and The Land of the Oratunga (1932) – were strikingly treeless, the opposite of his best-known paintings where gum trees featured centre stage.

Approaching the Flinders Ranges from the south, I was on the lookout for Patawarta Hill, described as a “fine bold object in the landscape”. And so it was that on climbing Wilpena Pound’s 923-metre Mount Ohlssen Bagge, the distant pyramidal shape on the northern skyline some 65 kilometres to the north could only be that striking hill.

I subsequently sought permission from the Heysen family to access the Flinders Ranges correspondence between Sir Hans Heysen and his wife Sallie, held at the National Library of Australia. My purpose? To find out what these unpublished letters might reveal about his encounters with the landform he affectionately called “Old Pat”.

All up, Hans Heysen spent an estimated 11 months in the Flinders Ranges between 1926 and 1949, mounting 12 expeditions to the semi-arid interior, one of which was washed out before it got underway. While his first trips north were in spring – September, October and November – the autumn months of March, April and May proved to be the most conducive for sketching and painting.

Heysen posted letters to his wife and family on a weekly basis, and more frequently as opportunities arose. His correspondence grew like topsy during the week with Hans scribbling down his thoughts as time and energy permitted. They ranged from a one-page missive to the longest at 14 pages. And he was in the habit of scribbling an extra note at the mail stop or penning an immediate response to incoming mail rather than have Sallie wait another week or more.

Hans wrote home from the Flinders Ranges with little or no attempt to gloss over his feelings, be they over the moon or utterly downcast. This contrasts with correspondence to his art world compatriots Lionel Lindsay and Sydney Ure Smith which, according to Colin Thiele, were routinely drafted and rewritten before Hans was satisfied. As off-the-cuff correspondence, the Far North letters provide intimate and at times surprising insights into a man widely described as reserved, self-effacing and the last person on earth to blow his own trumpet.

Each page of Hans Heysen’s missives – mostly written in pen and ink but occasionally in pencil – were peppered with insights into the daily routine of the artist, including the challenges he encountered in the northern lands. They respond to Sallie’s news of the children, including their illnesses and scholastic and sporting successes, with Nora’s commissions coming in for a mention on his late 1940s trips. They provide advice to Sallie, his partner in business, on prices to be charged for this or that artwork and other matters requiring resolution. They also register his sadness at the passing of notable local identities, reminders of his own immortality no doubt.

Underpinning all his letters was his enduring love for Sallie and gratitude for her efforts to contribute to the success of his painting expeditions. Clearly he was missing his mate in the Far North, to the point where he blamed his characteristic insomnia on her absence. His profuse thanks aside, a second undercurrent to his correspondence was his ongoing anxiety about her health and concern she was overdoing things by hosting a whirl of social activities on top of raising their family of eight children.

You might like

It’s hard to know what store Hans put in the quality of his correspondence. Was he sending himself up when writing home to Sallie in 1933: “You will be getting tired of reading this long rig ma role. – so I will stop.” He was equally self-deprecatory when he penned in 1947, “But now dear heart ‘this brilliant chat’ comes to a close – the day is drawing in & tomorrow we move out early”.

The pyramid and the circle

So what do these letters reveal about Hans Heysen the artist, the husband and father, and his abiding love of the Far North? The legendary painter of gums – so drawn to trees he affectionately referred to as “old stagers” with “their old secrets” – also had a thing for hills, none more so than the primitive and peculiar landforms of the Flinders Ranges.

On his first trip to northern South Australia in 1926 he no doubt greeted fondly the statuesque river red gums lining intermittent watercourses. And while the sub-species were very similar to those growing around The Cedars, the landscape they grew in was anything but familiar.

“I found the contours of the hills extremely interesting to draw – clear edges without much foliage, never ‘sluggish’ nor yet too spiky – always a beautiful balance between the pyramid and the circle.”

Such was his interest in the contours of the high ground that, with the exception of tree-lined creek beds framing distant hills, the majority of his landscapes were treeless, to the point where Heysen appears to have ‘airbrushed’ them out of the picture. Once in the Far North, the anatomy he was primarily interested in – the all-important bedrock – became his primary obsession.

He was enchanted by the citadel-like walls of the Flinders Ranges, nowhere more picturesquely expressed than in the rampart Elder Range and encircling Wilpena Pound. The ranges aside, he remained fascinated by a handful of ‘brutalist’ landforms that resembled the ruins of ancient man-made ziggurats, including a prominent hill near the start of Brachina Gorge, and Patawarta Hill to the north of Blinman.

Equally he was drawn to the workings of “Dame Nature” in miniature. His interest went beyond the “bare bones” of the land, as he wrote to Lionel Lindsay in 1928:

“The washouts are a decided feature of the landscape, caused by heavy and sudden summer rains, due to thunderstorms. These fissures vary in colour from pale gold to deep red and chocolate, and are everywhere.”

Accordingly, some of his most famous paintings in the Flinders Ranges celebrate spectacularly scoured-out erosion gullies. Art historians had noted Heysen’s fascination with the inner workings of the land long before he travelled to the Far North. His reverence extended to sand mining operations, stone quarries and the cliffs carved out by the downcutting Murray River.

Purple mountains of the North

The antiquity of the Flinders Ranges clearly touched Heysen. He was intrigued by the broken-down stumps of a landscape that 500 million years earlier had outmatched the Himalayas in height. But not just any scene would do. Waiting for the feeling to come, Heysen was like a tuning fork, ever alert to the right combination of landform and lighting to trigger the all-important alchemy.

Subscribe for updates

On his first visit in 1926, Hans Heysen embraced the “revelation of the Flinders” as he familiarised himself with “the purple mountains of the North”. It was, however, a revelation of the most unsettling kind, with the renowned and much-feted artist unable to capture what he was seeing and having to content himself “with a general survey of the district, its forms, light, and character”.

Such was the exotic nature of the landscape and the difficulty of painting clear space that Heysen was forced to jettison his customary palette of colours and develop an entirely new one. It was not an easy graduation, one that his letters reveal he was still grappling with in the early 1930s, despite the acclaim that had greeted his Far North exhibitions.

With pencil or charcoal in hand, Heysen was on steadier ground. As he’d always maintained, “Draughtmanship is the art of recording fast what the eye sees. Training the eyes and the hands to do this is one of the most important needs of the artist. And he must have a memory that allows him to record not only what the eye sees but what the mind behind the eye sees, is the important thing.”

Lost to public view

While a small number of his northern paintings and drawings have come to public attention over the years – principally featuring Brachina Gorge, the Aroona Valley and Patawarta Hill – the majority are unknown to the wider community.

The reasons are twofold. While a sizeable number of his drawings, studies and, to a lesser extent, paintings are held in the public collections of state and national art galleries and libraries, most galleries are not in a position to exhibit more than a handful of Hans Heysen paintings, with the majority in storage.

Even less accessible are the multiple watercolours, oil paintings and charcoal and pencil masterpieces held in private collections the world over and also lost to public view.

With the assistance of public art galleries and private auction houses which made available reproduction quality images, Hans Heysen Was Here brings to light the breadth, depth and diversity of the prolific output inspired by Heysen’s trips to the Far North. In some small way it turns the tide on the great forgetting of an artist who fell out of fashion during the 1960s and 70s when Modernism and contemporary art came to the fore, sidelining so-called representational artists, as described by Lou Klepac in Hans Heysen.

Hans Heysen defended himself on this score, describing his modus operandi of building a painting from careful observation. In interviews with Colin Thiele and Ian Mudie during 1966 and 1967 he explained:

“It is stupid to think you are painting an actual photographic reproduction of what you see before you. An artist is never really free – he is always captured by what is going on inside his mind, and he is bound up with it until he has expressed his idea.”

It is therefore ironic that when he first exhibited his paintings of the Flinders Ranges, they were regarded as strikingly unusual and modern in their own right.

Much has changed in the Far North since Heysen’s last visit. When Heysen was scouring the land for painting spots between 1926 and 1949, the semi-arid landscape had been subject to almost 80 years of livestock and agricultural pursuits. Overstocking, coupled with exceptionally dry conditions, meant that what Hans was observing and what current-day visitors to the Flinders Ranges get to see, are a world apart.

The South Australian government’s purchase of the Wilpena and Oraparinna stations in 1970 to create the Flinders Ranges National Park has allowed a comeback of the typical vegetation of the northern lands. So it was that Heysen was capturing a snapshot in history when the bare bones of the land, for better or worse, were on show in all their gaunt grandeur and glory.

Hans Heysen did a superlative job in bringing the desolate starkness and majesty of the Far North to his fellow Australians before colour photography was readily available. His numerous letters home via the Hawker, Blinman and Quorn post offices round out that snapshot. Regardless of his private estimation of his literary prowess, Hans Heysen’s eloquent, expressive and emotional letters provide an alternative avenue for his inner poet and give us a glimpse of the private man behind the paintbrush.

This is an edited extract from Hans Heysen Was Here (Wakefield Press) by Barbara Cameron-Smith, out now.

Barbara Cameron-Smith’s career spans more than 40 years researching and delivering natural and cultural heritage interpretation projects for the public and private sectors, including exhibitions, publications and outdoor interpretive signage.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence