‘History isn’t a straight line towards enlightenment’: First-time novelist navigates Colonel Light’s layered identities

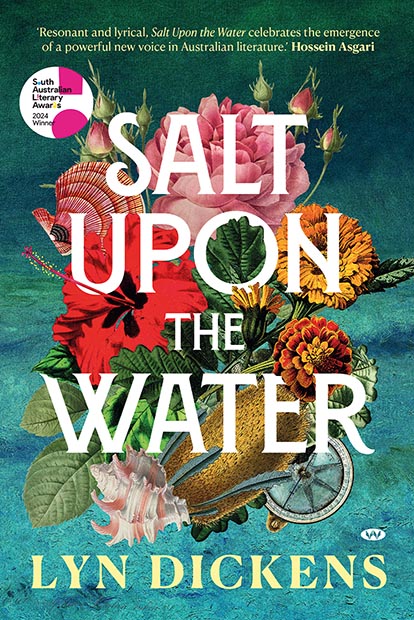

Lyn Dickens’ award-winning debut Salt Upon the Water reveals the fascinating, cosmopolitan and complicated past of Adelaide’s famed surveyor and designer Colonel William Light.

Debut novelist Lyn Dickens’ Salt Upon the Water reveals the fascinating and cosmopolitan past of Adelaide’s famed surveyor and designer Colonel William Light.

When Lyn Dickens first set eyes on a self-portrait of Colonel William Light, she was startled by what she saw. “I just stopped and looked at it,” she tells InReview. “Something about his face… I thought, he looks like someone like me.”

That moment of recognition became the spark for Salt Upon the Water, Dickens’ lyrical debut novel and winner of the 2024 Arts SA Wakefield Press Unpublished Manuscript Award. Subsequently acquired by Wakefield Press and published this month, it reimagines Light – long celebrated as the surveyor who designed Adelaide’s grid layout and surrounding Parklands – as a man increasingly constrained by social conventions as the cosmopolitanism of the late Regency period rolled into the more purist Victorian era.

“I’d always assumed he was just an English surveyor,” Dickens says. “I never thought about his heritage. Then I discovered his father was the Governor of Penang and it suddenly clicked: Adelaide was designed by a mixed-heritage Asian man. And somehow that’s not part of our public story.”

Salt Upon the Water places this fascinating revelation at the heart of this historical narrative that spans the geographic sweep of the British colonial system, from England to Australia via India and Malaysia. Its female protagonist, Clarissa FitzRoy, a woman of mixed ancestry, travels from London to South Australia to confront Light in her search for information about her mother in the wake of a turbulent family history of disinheritance, dispossession and exile.

"Adelaide was designed by a mixed-heritage Asian man. And somehow that’s not part of our public story."

You might like

Dickens’ insight into the emotional and economic toll of systemic racism stems from her own complex family heritage.

“My dad’s side is Anglo-Celtic Australian, and my mum’s side is Singaporean Peranakan Chinese with some Malaysian connections,” she explains. “That background made me curious about how people with layered identities navigate rigid societies – and how those societies decide who belongs.”

That tension, she argues, has deep historical roots. “When Light was born, the late 18th century was actually quite a cosmopolitan time. There was more acceptance of people of mixed heritage, especially around Asia,” she says. “But by the time he died, the British Empire had become more institutionalised, more controlling. The world had grown less tolerant. You can see the racial divisions hardening as the century went on.”

Dickens sees that shift from hybridity to hierarchy as a warning for the present. “History isn’t a straight line towards enlightenment,” she says. “It moves forward and back. We like to think we’re more progressive every decade, but we’re also living through periods of regression. You can see it happening now – there’s a backlash against diversity, a discomfort with complexity. It feels familiar.”

Writing Salt Upon the Water during her PhD, Dickens spent years immersed in archives, libraries and letters.

Subscribe for updates

“Light’s public documents from Adelaide sound dry and pragmatic – almost bitter,” she explains.

“He comes across as unhappy and misunderstood. But when I looked at his early life, I found this swashbuckling romantic. He was a poet, an artist, a soldier in the Napoleonic Wars, a lover. It struck me how people can be both idealistic and compromised, bold and weary. That became the heart of the novel.”

She’s quick to note that the story is deeply fictionalised.

“Clarissa is invented, but she’s grounded in real women from the era,” Dickens says, drawing her inspiration from historical figures such as Kitty Kirkpatrick (a woman of Indian and English ancestry featured in William Dalrymple’s research) and from reformist writers such as Letitia Elizabeth Landon and Caroline Norton.

“There were so many women pushing against the grain. Clarissa’s journey is about claiming a self that doesn’t fit into neat categories of race, gender or class.”

The novel’s use of water imagery, from ocean voyages to flashes of folklore that spark against the book’s realism, offer a way to think about identity. “It started intuitively,” Dickens says. “But it became a metaphor for Clarissa’s sense of self – something that can move between worlds. Water is fluid, it connects, it refuses borders.” Dickens laughs when asked if she set out to use magical realism. “Maybe a little,” she says. “It was also about finding other ways of knowing – not just the categorising, colonial way, but something more intuitive.”

"There were so many women pushing against the grain. Clarissa’s journey is about claiming a self that doesn’t fit into neat categories of race, gender or class."

Dickens’ own experiences living and studying across continents give the novel its sensory authenticity. “Every place in the book is somewhere I’ve spent meaningful time,” she says. “From London and Venice to Penang and Calcutta – those journeys helped me, and my nostalgia for them especially helped me imagine Light’s dislocation and longing.”

Dicken’s began writing the book in 2018 and finished it between lockdowns and raising small children. The novel’s long gestation paid off with Salt Upon the Water earning praise for its lyricism and moral complexity. But Dickens admits she was anxious about revisiting a local hero.

“People in Adelaide have strong feelings about William Light, which is understandable,” she says. “The Parklands are a beautiful legacy. Green space is so important for a city’s health. But I hope people can see him as human – flawed, complicated, fascinating.”

This assured debut sets itself apart in its refusal to flatten history. “I came away feeling that Light tried to be ethical within the world he lived in,” Dickens says. “He wasn’t perfect, but he was thoughtful – and he was shaped by a world that didn’t always have space for someone like him.”

Salt Upon the Water (Wakefield Press) is out now. The book will also be launched at the State Library of South Australia on November 6 from 6pm.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence