Summer Reading: South Australia’s writers and readers share their 2025 highlights

From Hannah Kent to Adelaide Writers’ Week director Louise Adler, we’ve polled the state’s writers, publishers, reviewers and booksellers about their year in reading.

As we prepare to close the book on 2025, it’s time to share notes on which titles touched, taught or transformed us over the past 12 months.

I loved putting together this Best Books list for another year. The only rule I gave these writers, publishers, reviewers and booksellers was that their chosen book must be published in 2025, and that they couldn’t choose a book they’d worked on. A couple cheated on the first point. And a few snuck in extra titles. But how could I begrudge their passion?

I read (and loved) more new fiction as opposed to nonfiction this year, which is represented in my picks. And as I’m making the rules, I decided to share my top two Australian and overseas books. I’ll probably wake up the day this is published and regret the excellent books that didn’t make it. But oh well!

I followed the rules about not choosing books I worked on, but I will quickly tell you about two them, by Adelaide writers. Natalie Harkin’s Apron-Sorrow/Sovereign-Tea (Wakefield Press) is a must-read history of Aboriginal women’s domestic labour in South Australia, accompanied by artwork, poetry and oral histories. And Carol Lefevre’s Bloomer (Affirm Press) is an exquisite memoir in essays about ageing, set in the year she turned seventy, against the backdrop of her garden and its changing seasons.

Reading this, I hope you, like me, get ideas to help make your own summer reading pile – or Christmas list.

My favourites of 2025

The Transformations, Andrew Pippos (Picador)

This big-hearted (yet unsentimental), alternately wry and moving novel is set in 2014: a specific moment in the long death of broadsheet newspapers. Kind, damaged subeditor George is carefully solitary. Then the teenage daughter he had at nineteen relocates to Sydney and a connection sparks with journalist Cass, who’s experimenting with an open marriage. These characters’ personal transformations unfurl alongside a changing media landscape. And I was unsurprised to see Pippos has worked as a subeditor; his details (and their execution) are pitch-perfect.

Plastic Budgie, Olivia De Zilva (Pink Shorts Press)

I was hooked by this brilliantly sad-funny Adelaide debut autofiction from its opening pages. In diamond-sharp sentences, De Zilva (named for Olivia Newton-John) combines sardonic humour with poignant, incisive recollection, sharing stories about her loving dysfunctional family, internalised racism, shocking school bullying (and teacher neglect), loneliness, inherited trauma and finding community at university. This is the most exciting new Australian voice I’ve discovered this year – and a testament to the strength of new local publisher Pink Shorts Press.

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: From China to America, a True Story of Abduction, Adoption, and Separated Twins, Barbara Demick (Text Publishing)

Barbara Demick is a masterful narrative journalist. In this addictively immersive book, she deftly tells the dark history of international adoption in China during the One Child policy through dogged reporting and fascinating personal stories. She interviews Chinese families whose children were forcibly adopted and American families horrified to discover the children they thought they were “saving” had been stolen and basically sold to orphanages. The focus is the incredible story of identical twins, separated when two-year-old Fangfang was abducted from her village, reunited through Demick’s sleuthing and organising.

The Mobius Book, Catherine Lacey (Granta)

I’m now obsessed with Catherine Lacey, after reading this startlingly original, very writerly memoir/fiction – it’s two books in one, to be read in any order – about the aftermath of a devastating long-term relationship breakup. (The ex, another writer, emailed from another room of their house to tell her he “met another woman last week and now it’s over”.) These deeply human shards of self-interrogation reminded me of Helen Garner, or Sarah Manguso – a character in the memoir half (as is Geoff Dyer).

Jo Case is senior deputy editor, Books & Ideas, at The Conversation, and wrote the InReview column Diary of a Book Addict for nearly six years. This year, she co-edited, with Clem Bastow, Someone Like Me: An Anthology of Non-Fiction by Autistic Writers, published by UQP in Australia and Verve internationally.

Best books of 2025, as chosen by local authors

Hannah Kent

Discovering wildly talented writers at the beginning of their careers is such a pleasure for me as a reader. One of my favourite books this year was such a debut. The Sun Was Electric Light (UQP), by Australian poet Rachel Morton, follows a woman who moves to Guatemala in the hope of attaining the happiness she felt there years earlier. The themes of connection and disillusionment are rendered with nuance and complexity, but it is Morton’s prose, unadorned and magnificent in its clarity, which announces her astonishing talent.

Hannah Kent’s latest book is Always Home, Always Homesick. Her debut novel, Burial Rites, was in the top 10 of ABC Radio National’s Best Books of the 21st Century poll.

Pip Williams

You might like

What a joy and revelation it was to read Hannah Kent’s Always Home, Always Homesick (Picador), a memoir about the year she spent in Iceland and the extraordinary novel that was born from that experience: Burial Rights. Hannah’s memoir is a beautiful, generous and rare insight into the life of a book and the making of a writer – a gift to readers and writers alike.

Pip Williams’ latest book is The Bookbinder of Jericho. Her debut novel, The Dictionary of Lost Words, was in the top 10 of ABC Radio National’s Best Books of the 21st Century poll.

Lainie Anderson

“There is something sinister about how we were made to feel. Like our bodies were dirty, yet we were to clean their homes.” Combining poetry and oral history, visual imagery and archival analysis, Natalie Harkin’s sublime Apron-Sorrow / Sovereign-Tea (Wakefield Press) tells the hidden story of Aboriginal women’s domestic labour and servitude in South Australia. The memory stories are both heartbreaking and uplifting, revealing women of agency, wit and grit. The facts are infuriating: in 2025, families are still denied access to Aborigines Department records.

Lainie Anderson is the author of two Kate Cocks mysteries, most recently Murder on North Terrace.

Rebekah Clarkson

Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me (Hamish Hamilton) is a study on love in its most complicated form. We must all reckon with our parent/child relationship to some degree, but for some it is deep work for a lifetime. Roy’s memoir achieves what therapeutically inclined books about these relationships rarely can. Equally – and equally fraught – it is a deep dive on Indian politics, and the internal and external trajectory of a writer. Profoundly moving, and full of Roy’s wry, infectious humour.

Rebekah Clarkson’s Barking Dogs has just been reissued in a new edition. She is also co-author of This is What it Feels Like.

Alex Cothren

In Andrew Roff’s Here Are My Demands (Wakefield Press), the luck runs out for The Lucky Country. It’s 2058, and automation has triggered mass unemployment and rolling uprisings. Idealistic public servant Maggie Garewal has a solution and mandate, but she’s chewed up by the bureaucratic gears of an Australian democracy only further fractured by augmented reality. Roff’s deadpan skewering of this nation’s ‘Don’t know? Vote no’ political apathy catapults him to the top shelf of Aussie speculative writers working today.

Alex Cothren’s latest book is Playing Nice was Getting me Nowhere.

Tracy Crisp

I was determined to break my phone habit this year and replace my scrolling with reading. So I’ve read a lot, making choosing just one difficult. I’m going to cheat a little and say the Elizabeth Harrower biographies by Susan Wyndham – Elizabeth Harrower: The Woman in the Watch Tower (New South) – and Helen Trinca’s Looking for Elizabeth (Black Inc.). They are two very different approaches to exploring Harrower’s fascinating family, social and creative lives.

Tracy Crisp’s Pearls will be published in March 2026.

Olivia De Zilva

Matthew Hooton’s Everything Lost, Everything Found (Fourth Estate) made its way to me at a very pertinent time. After experiencing a strong period of change, the book vindicated my feelings of loss and grief for a time I could never revisit. This twisty epic takes place across two different timelines – “before” in Henry Ford’s luscious capitalist bounty in the Amazonian rainforest, and “after” in the vast wasteland he left behind in Detroit, Michigan. Following protagonist Jack from childhood to old age, the book questions who people become, as C.S. Lewis would say, after we exit the wardrobe. Hooton talks about time as different segments of the tide: gorgeously unattainable and gone in an instant.

Olivia De Zilva is the author of Plastic Budgie and Eggshell.

Walter Marsh

Sinead Stubbins is one of several writers who did great work throughout the 2010s youth media boom (and subsequent bust) and have now emerged from the shuttered content mines as proper novelists. Her debut novel Stinkbug (Affirm Press) is a delight: an often-bonkers workplace satire crammed with thoughtful and devastating observations on labour, gender, and relationships. I had to stop sending passages to friends and former colleagues because it all felt a little too on the nose.

Walter Marsh’s latest book is The Butterfly Thief. He is editor of InReview, South Australia.

Rachael Mead

I devoured Katabasis by R.F. Kuang (Voyager), and its fusing of mythological and philosophical research with a pointed critique of academic culture. It’s a modern-day Divine Comedy, with Dante’s journey replicated by two post-grads trying to save their thesis supervisor from hell. This addictive novel has intellectual heft in its exploration of afterlife mythologies, while Kuang’s wry humour keeps everything deliciously irreverent.

Another book I found impossible to put down was Chloe Dalton’s account of finding and raising a baby hare. A gorgeous piece of nature writing, Raising Hare (Canongate) captures the modern state of entanglement between humans and the wild with quiet and deeply empathetic intelligence.

Rachael Mead’s latest book is The Art of Breaking Ice. She is a regular reviewer for InReview and co-hosts regularly literary event Dog-Eared Readings with Heather Taylor Johnson.

Jennifer Mills

I went looking for solidarity in my reading this year, and was grateful to find Omar El Akkad’s clarifying One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This. His honesty gave me a much-needed hit of oxygen in a time of stifled expression. Laila Lalami’s eerily familiar dystopia, The Dream Hotel, fights just as hard to defend the inner life against algorithmic control.

Jennifer Mills’ latest book is Salvage. She is chair of the Australian Society of Authors.

Molly Murn

I’ve read some electrifying books this year, including Cure by Katherine Brabon, The Sun Was Electric Light by Rachel Morton, Charmaine Clift’s Honour’s Mimic, Barbara Hanrahan’s Annie Magdalene, Catherine Lacey’s The Mobius Book, Big Kiss Bye Bye, David Szaly’s Flesh, and recently, Bread of Angels by Patti Smith.

But if I am forced to choose just one book to mark out 2025, it would be Han Kang’s We Do Not Part (Penguin). I still think about the snow, and the black trees, and the birds, and the dreamlike sequences as a woman travels to the remote island of Jeju in Korea on a rescue mission. It is in extraordinary and poetic exploration of artmaking, massacre and memory.

Molly Murn is the author of Heart of the Grass Tree. She is manager of Matilda Bookshop.

Andrew Roff

Salvage (Picador) is literary speculative fiction that speaks to our present moment – of plutocrats, preppers and seemingly inevitable catastrophe. Despite that, it’s a deeply hopeful story.

Human resilience is built on interconnection. Jennifer Mills shows us how, as things get harder, we could choose to build and support community. The alternative is to float adrift, beyond help or hope. A gripping read that’s also good for the soul.

Andrew Roff’s latest book is Here are my Demands.

Heather Taylor Johnson

Subscribe for updates

In a year of reading books about woman who’ve split from their partners (currently enmeshed in The Mobius Book by Catherine Lacey and loved last year’s Splinters by Leslie Jamison), my favourite book this year was Sarah Manguso’s Liars (Picador). Snippets make the story, which is messy and poetic, a wonderful combination. Also, here for Jessica White’s ecobiographical essay collection Silence is My Habitat (Upswell).

Heather Taylor Johnson’s latest book is Little Bit. She is a regular reviewer for InReview and co-hosts regularly literary event Dog-Eared Readings with Rachael Mead.

Vikki Wakefield

I rarely surrender to a book I suspect will destroy me (I go in with trepidation, the same way I inch into an unheated pool), but Charlotte McConaghy’s Wild Dark Shore (Penguin) pulled me under. It can be easily read as a gripping eco-thriller, or a far more intimate contemplation on human resilience and resistance – a story about broken people, standing at the edge of the world, facing the end of the world.

If that sounds bleak, it’s not. Wild Dark Shore is ultimately hopeful and uplifting in ways I didn’t see coming.

Vikki Wakefield’s latest book is To the River.

Allayne Webster

My choice is A Good Kind of Trouble by Melanie Saward and Brooke Blurton (Harper Collins). This contemporary coming-of-age novel with queer and Indigenous rep unapologetically centres its teen audience, luring readers with a fresh, authentic, energetic voice in Jamie as she navigates school, family, friendships, and first loves – all portrayed with feisty believable heart.

Teen Me would have devoured it. More of this on the Aussie curriculum please!

Allayne Webster’s latest book is Maisy Hayes is not for Sale.

K.A. Ren Wyld

I’m currently reading The Gowkaran Tree in the Middle of Our Kitchen (Allen & Unwin) by Shokoofeh Azar. Similarly to when I read her debut, The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree, I was hooked from the start.

Shokoofeh, an Iranian journalist who sought refuge in Australia, is an astute storyteller who conjures heady, lyrical prose that merits a deliberate read. The narrative weaves decades of a family’s life, dreams and loves into a broader context of political and social upheaval, with ample wonderous happenings to enchant readers.

K.A. Ren Wyld is co-editor, with Dominic Guerrera, of The Rocks Remain: Blak poetry and story.

Best books of 2025, as chosen by publishers, critics and literary leaders

Louise Adler

My book of 2025 is Mohammed El-Kurd’s Perfect Victims (Haymarket Books). Kurd has written an homage to the Palestinian people – their resistance and their right to imagine a future.

His anguished question is unavoidable: “how many of us could have done something, anything and did not?”

Louise Adler is director of Adelaide Writers Week.

Alex Dunkin

Six Conversations We’re Scared to Have by Deborah Frances-White (Virago) is a fascinating discussion on such topics as reassessing controversial historical figures and “cancelling” in comedy.

The book is a conversation starter and, while not stating hard boundaries or rules, it focuses on reframing debates, details context from historical examples, and pushes against restrictions on freedom of speech and critical thought.

An interesting section early within the book looks at the evolution of empathy – and posits that, rather than it disappearing, it’s intensifying.

Alex Dunkin is director of Buon-Cattivi Press.

Amelia Eitel

My selection is Ash by Louise Wallace (Allen & Unwin). This book blazes and seethes with an elegant fury. A fury many will recognise as their own. Issues of family, work, and environment are explored. A thread of a second story flows in the footnotes. A deeply moving book I will think about as long as I have working memory.

Amelia Eitel is owner of Imprints Booksellers on Hindley Street.

Farrin Foster

My choice is Plastic Budgie by Olivia De Zilva (Pink Shorts Press). Olivia has such a strong voice, and her debut really demonstrates her range in capturing different emotions and stages of life while staying true to that voice. I also loved the form of this book, which builds things up in layers and then slices through its own foundations. It’s both very clever and very funny. An honourable mention, if I can, to Dominic Amerena’s amazingly well-crafted and twisty and fun (in an off-putting way) I Want Everything (Simon & Schuster).

Farrin Foster is editor of Splinter Journal.

Megan Koch

John Patrick McHugh’s Fun and Games (Fourth Estate) is as viscerally evocative a portrait of late-teenagehood as I’ve ever read. The novel spans a restless summer on the Irish West Coast in 2009, as protagonist John and his cohort await the exam results that will determine their futures. I loved it for its pitch-perfect dialogue, and for what McHugh captures of young male friendships: the posturing, the tentative tenderness, the insecurities and resentments, and the comradeship entangled with loneliness.

Megan Koch works at Marion Libraries and is a regular reviewer for InReview.

Margot Lloyd and Emily Hart

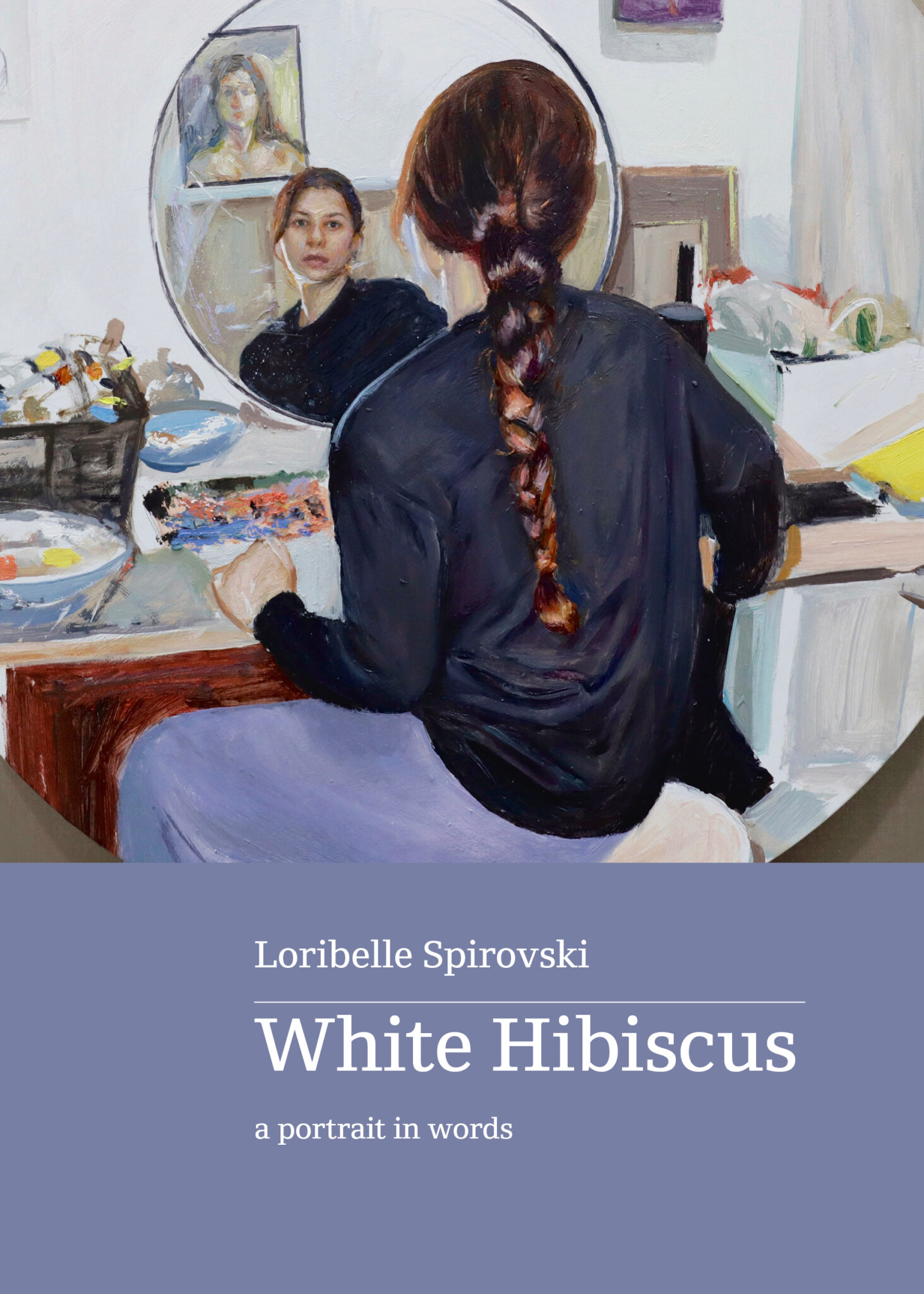

Loribelle Spirovski won the 2025 Archibald People’s Choice Award for White Hibiscus, and this gorgeous poetic memoir – published by fantastic independent WA publisher Upswell – shows her creative range. Ostensibly a chronicle of a cruise trip she takes with her pianist husband, White Hibiscus grows in scope as the trip goes on, Spirovski finding echoes and memories of her childhood in the Philippines and her formation as an artist. Spirovski kindly allowed us to feature one of her paintings for a March 2026 cover.

Margot Lloyd and Emily Hart are the directors of Pink Shorts Press.

Maddy Sexton

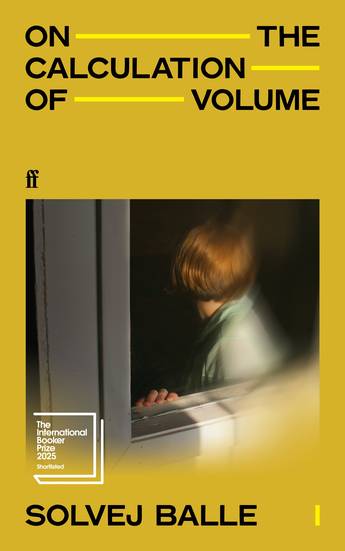

On the Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle (Faber) follows antiquarian bookseller Tara, who wakes up one morning to discover she is reliving the 18th of November. Unlike other Groundhog Day time-loop novels, Tara is less focused on escaping the loop than on how it feels to be stuck in time – the isolation of living more and more new days, while everyone around her experiences the same day for the first time; the moral dilemma about whether to tell her loved ones about her predicament, knowing the distress it will cause; and the impact her repeated days have on her environment. It’s repetitive and slow: but compulsively readable.

Maddy Sexton works in editorial and is head of YA at Wakefield Press.

Anna Solding

Being asked to nominate my favourite book published in 2025 made me realised how few new releases I read. However, there are a couple of fairly recent titles that have stuck vividly in my mind: All Fours by Miranda July (Canongate) and Intermezzo by Sally Rooney (Faber). Both are literary novels about the convoluted ways that people deal with sex and relationships, what polyamory can be and how the capability of love and attraction is endless. I read to feel, and both of these books pound on your heart and beg you to be let in.

Anna Solding is director of Midnight Sun Publishing

Revisit more of InReview’s 2025 literary coverage here

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence