MAKE or break: national craft and design prize explores artists’ evolution versus ‘innovation’

From a couch with attitude to playfully esoteric glass work, an exhibition of finalists in the MAKE Award for Innovation in Australian Craft and Design showcases original and thought-provoking work in the overlap between craft and design.

Although the $35,000 MAKE Award for Innovation in Australian Craft and Design was conceived as a biennial event, this second iteration now showing at JamFactory will in all probability be the last. After more than 60 years, the award’s host organisation, the Australian Design Centre (ADC), Sydney, has been defunded and is facing closure. Originally formed as the Crafts Council of NSW to represent the interests of its membership of potters, weavers, jewellers, glass blowers, wood workers and other craft practitioners, it moved with the times to be re-christened Object: Australian Centre for Contemporary Craft and Design in 1998, and then Australia Design Centre in 2015.

Media favoured by craft practitioners when the ADC was established – clay, metal, glass, textiles, wood – are still often preferred the media of choice for the 36 finalists in the MAKE Award, but there the similarity ends. Craft traditions of skilled object-making were, and still are in many cases, based on the ethos of thinking through making, and truth to materials, with the form evolving from the maker’s deep understanding of their medium. From the mid 1990s Craft’s new bedfellow, Design, started to play an increasingly dominant role, due in no small part to trends in arts funding policies and tertiary training. Contemporary designer/maker/artists are incorporating skilled making but also choosing to work with the media and advanced manufacturing processes which most effectively realise their concept design.

If there was a Venn diagram of the relationship between these two fields of craft practice and design in the broadest sense of the terms, the shaded area of overlapping circles would be slim indeed, and yet the MAKE Award demonstrates that it has been in this narrow overlap that thought-provoking and original work has been created. Both the award-winning Noctua lamp by Sydney artist jeweller Cinnamon Lee and the second-prize winner, SOFA3744 by Adelaide furniture designer and JamFactory alumni, Jake Rollins, are exemplars of an inventive design-led approach.

There is admirable ingenuity in Lee’s exquisitely fabricated hybrid object, which is a sculptural metal lamp, partially fabricated by digital processes, and designed to hold a detachable titanium and silver brooch, embedded with sapphires. When the lamp’s light is projected through the brooch, its pattern of sapphires and metal mesh creates the shadow image of a bogon moth on the wall. This brooch has a stand-alone beauty as a wearable object when detached from the lamp, but this is not apparent in the exhibition itself. It is difficult to view the brooch while the lamp is illuminated and the resulting work lacks impact (this piece would have been enhanced by the inclusion of the explanatory video that can be found on Lee’s website).

Rollins’s highly experimental SOFA3744 is a couch with attitude, so named as it is made from 3744 recycled golf balls, held in place by tensioned cord through a process of triaxial weaving. It exudes confidence and a playful joie de vivre. In his related body of recent work, GolfWeave, Rollins has been experimenting with creating objects that can be dismantled, with the components then repurposed into new works. Testing the experience of sitting on tensioned golf balls is expressly forbidden during the exhibition, although Rollins confirms that this is indeed possible, in principle. Functionality aside, SOFA3744 is a successful hybrid of sculpture and experimental design, with possibly a nod to that famous but very different predecessor, Marc Newson’s Lockhead Lounge (currently on display at AGSA).

You might like

The interdependence between the thinking process of design and the making process of craft is not dissimilar to the relationship between software and hardware. This relationship is embodied in a tantalising way by Canberra-based Filipino American artist glass artist Jeffrey Sarmiento in his sculpture, Encyclopaedia Self Portrait. With consummate mastery of his medium Sarmiento has kiln-cast a translucent life-size glass head, comprised of a complex layering of fragmentary and illegible texts, suggestive of the mind’s processing of external input. Encyclopaedia Self-Portrait meets the challenge of being highly resolved at both a conceptual and technical level.

Jeffrey Sarmiento, Encyclopaedia Self Portrait, 2025. Photo: Bullseye Glass Co / SuppliedAnother artist whose practice engages directly with this software/hardware duality is jeweller Zoe Veness, whose neckpiece, Solaris, is comprised of rag paper, folded in a myriad of mathematically complex configurations to form concentric circles. Over many years Veness has been fascinated with translating the beauty of mathematical systems into intricately folded neckpieces imbued with subtle gradations of tone from the hand-dyed paper. Solaris is a resolved work of exquisite beauty, conceptual complexity and meticulous crafting. However, as an exemplar of this larger body of Veness’s practice, perhaps Solaris did not meet the judging panel’s specific criterion in respect to ‘innovation’ – that over-used word so favoured by art funding bodies and their clients.

Similarly, other noted craft practitioners in MAKE who have evolved a signature style grounded in craft traditions of skilled making include ceramicists Kirsten Coelho and Neville French, and master glass artist Scott Chaseling. In each case we are seeing beautifully realised, technically accomplished pieces which may viewed in the context of a larger body of the artist’s work, rather than standing out as innovations, experiments or breakthroughs. While nearly all the work on display is firmly embedded in craft and design disciplines, it is refreshing to see two playful, esoteric sculptural works in glass and clay by artists Linda Draper and Julie Bartholomew, each taking an experimental approach to the intrinsic molten and malleable properties of these media.

Subscribe for updates

Not surprisingly, the latest generation of object makers are especially alert to such environmental issues as sustainable use of resources, nature conservation and imminent ecological threat. Unconventional, found and recycled materials abound, including Jane Theau’s startling fluoro-green basket form, Regeneration, woven from horsehair and copper wire; Blanche Tilden’s Satellite Necklace of salvaged camera lenses; and Melinda Young’s basket forms, unsettled vessels (Australian Settlers and Early Australian Utensils) made from unpicked and reworked vintage linen tea towels.

JamFactory alumni Bolaji Teniola’s gracefully poised Amphora is a successful exemplar of his experiments with waste timber shavings. Another JamFactory alumni Lotte Schwerdtfegar simulates a bleached coral formation in her hand built ceramic lamp, as an apparent lament for the impact of climate change. In her homage to natural beauty, Amulets for Moths, Vita Cochran has created intricately patterned moth embroideries with exquisite verisimilitude.

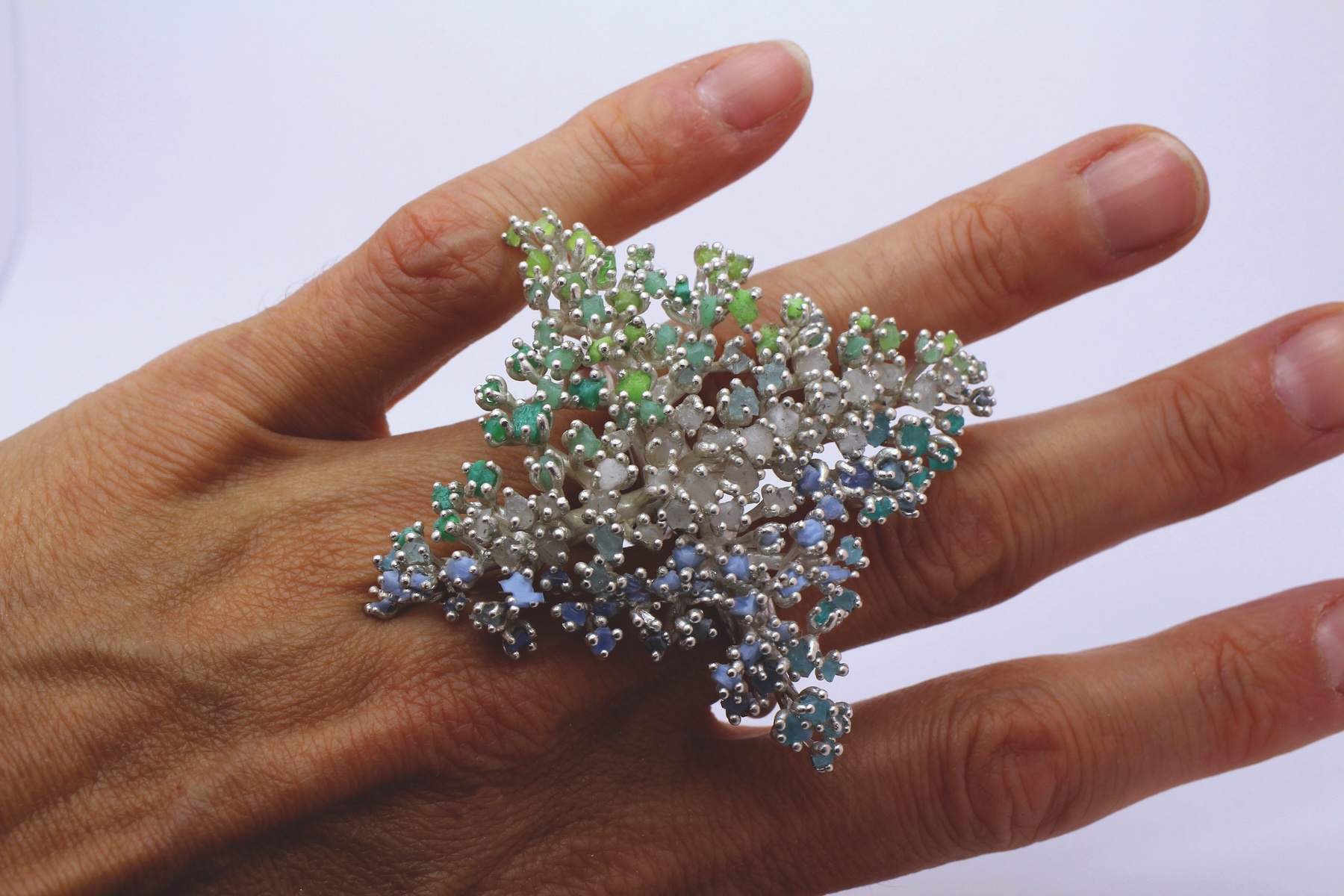

The gem-like sparkle of Laura Deakin’s spectacular double ring is achieved by a myriad tiny pieces of scavenged microplastic, set in sterling silver. Deakin has priced her ring at $8,370, as if it did indeed contain precious stones. An extreme case of the high price of eco-awareness is Emma Bugg’s necklace, Future Relic: A Material Memory. Her well-crafted and highly wearable necklace is so much more than it appears at first glance, and this might explain the high price of $38,610. It is composed of both inorganic materials, namely concrete and metals, and organic materials, including gum tree ash particles, and mushroom leather (from mycelium). An NFC (Near Field Communication) tag is embedded in the clasp. This necklace is designed as a time capsule, a message to the future, and the artist intends that rather than being held in a gallery collection, it should be returned to the earth, ‘buried, forgotten, and rediscovered’. This is certainly asking for a high level of commitment from prospective owners.

MAKE is a testament to how, across those six decades since ADC’s forbear organisation was founded, craft practice has changed almost beyond recognition, while still continuing long established traditions. It is a fascinating, thought-provoking exhibition, but not necessarily indispensable if this turns out to be its last incarnation under the ADC. JamFactory is certainly well placed to take up the reins if it wishes, but arguably the competitive prize exhibition as an approach to surveying the state of craft and design practice may have run its course.

Or alternatively, it needs to be done on a more ambitious scale, as is the case with Melbourne’s triennial Rigg Design Prize valued at $40,000, currently on view at the National Gallery of Victoria. This award is restricted to early career designers but has similar criteria, being for ‘ambitious works that reflect bold approaches to materiality, form and function’. The 2025 award, now in its tenth iteration, was won by Arrernte ceramicist Alfred Lowe.

MAKE Award: Biennial Prize for Innovation in Australian Craft and Design is now showing at JamFactory until April 12 2026

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence