If only I could see through your eyes … how the late great Lloyd Rees taught architects to see

The revered Australian artist Lloyd Rees inspired generations of architects and a new book traces his architectural work back to his Brisbane beginnings.

Among memorable moments at the recently closed Brisbane Writers Festival was when artist Lloyd Rees’s son Alan Rees, 91, took to the stage to relate his memories of his dad. There was already much love in the room. The revered Australian artist Lloyd Rees (1895-1988) grew up in Brisbane, and began his art career looking critically at our buildings.

It is in Brisbane, too, that author Ross Wilson begins this most recent book Lloyd Rees and the Architects about Rees with the early drawings and paintings – and Rees’s grand (and imaginary) architectural visions for our city.

At the book’s heart is a compelling narrative tracing Rees’s ongoing influence on architects and others, like art critic Robert Hughes, a result of his teaching role in art and art history at University of Sydney’s architecture faculty (1946-1986). Among his students are those who have shaped Australian buildings, cities and aesthetics – notably Andrew Andersons, Louise Cox, Philip Cox, Espie Dods, Richard Leplastrier, Malcolm Middleton, Andrea Nield, Lawrence Nield and Penelope Seidler.

It’s an impressive roll call of influential Australian creative thinkers and, while the concept for the book came from AndAlso Books’ publisher Matthew Wengert, it is an idea that Ross Wilson picked up and delivered with alacrity.

It’s an impressive roll call of influential Australian creative thinkers and, while the concept for the book came from AndAlso Books’ publisher Matthew Wengert, it is an idea that Ross Wilson picked up and delivered with alacrity.

Wilson is best known as a writer for television, with credits such as Miriam Margolyes — Almost Australian and The Swap to his credit. However, in this book he draws on his intrinsic knowledge, instincts and background from a family of architects that spans four generations: their work is integral to the Brisbane cityscape and to Queensland.

Ross’s great grandfather, Alex B. Wilson, established an architecture practice in Brisbane in 1884, and designed buildings that include historic Lamb House at Kangaroo Point, recently lovingly restored by Steve and Jane Wilson (no relation).

You might like

Ross’s father, Blair Wilson, designed La Boite Theatre in Petrie Terrace in 1972 and South Brisbane’s Greek Orthodox Church. Ross’s mother Beth Wilson was trained as a botanist and went on to become one of Australia’s leading landscape architects. Ross’s brother Hamilton Wilson is currently practising, best known for his work at universities in and around Queensland.

Ross Wilson’s first book, This Accidental Present, explores the complex history between the poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal and Brisbane’s Cilento family (AndAlso Books, 2023). Lloyd Rees and the Architects is his second. While it is informed by his research and interviews with the Rees family (Alan and Jancis Rees), what carries the reader forward is Wilson’s gentle narrative about the impact of Rees’s teachings on generations of architects, and the words of those for whom this teaching proved so influential.

Many books have been published about Rees’s art life – notably two monographs by art historian Renee Free (1972, 1990) and another biographical text by Free (1987), two books about his drawings by Lou Klepac (1978) and Art Gallery of New South Wales (1995), and two autobiographies (1969, 1985).

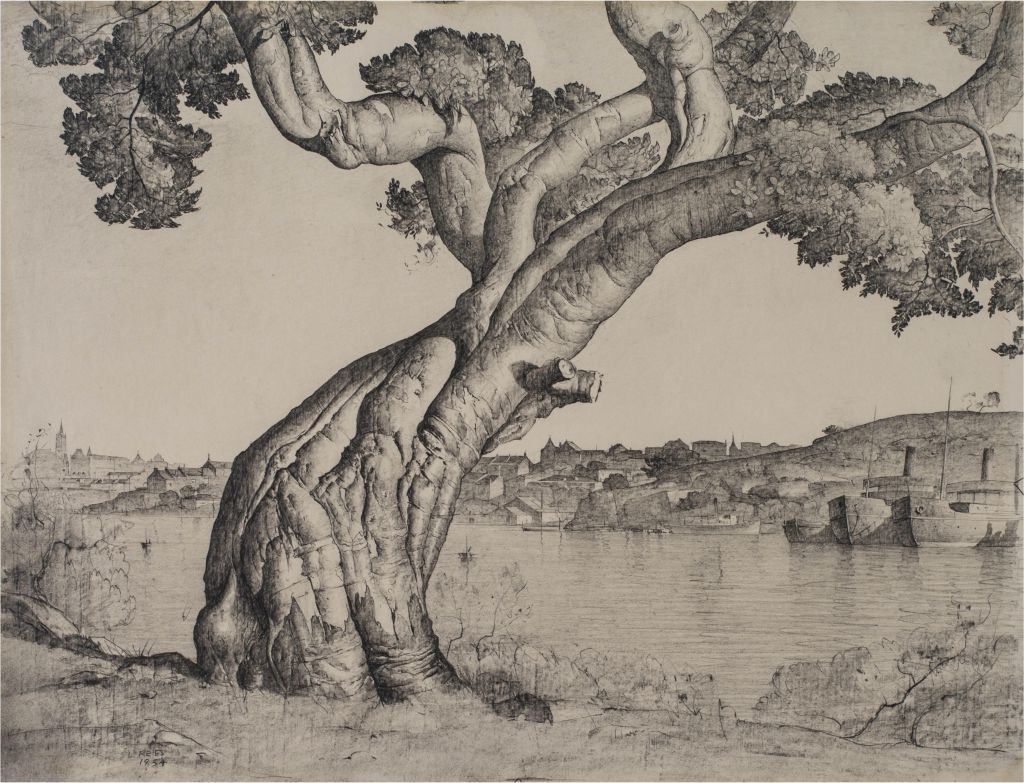

Rees’s health and mental struggles, loss of vision late in his life and the contribution that his paintings of “sculpted” light made to the Australian landscape tradition are well documented. What Wilson’s book adds crystallises just how powerful his teaching was to architects, artists and others who attended his courses. And the architects describe the impact that Rees’s shaping of their vision continues to make to place-making in Australia.

Central to this book is Rees’s lifelong interest in architecture and cities, and the longevity of his employment at the university. The relationship was “symbiotic” – according to his former student, architect Richard Leplastrier, Rees “taught us to love to draw”. At the same time, Rees found himself “buoyed by their energy”.

Subscribe for updates

As the decades progressed it wasn’t all smooth sailing, and Wilson sensitively details the resistance to Rees’s influence by some students during the foment of the 1960s, with opposition to his perceived traditionalist approach to art (in the light of new conceptual initiatives such as Christo’s 1968-69 wrapping of Sydney’s Little Bay). Despite the difficulties, Rees continued to teach until 1986, only two years before his death, aged 93.

Amid these decades, Rees’s ill health saw his hospitalisation at times. What Wilson’s book leaves us with is an impression of the artist’s abiding belief in the transformation inherent in art and beauty. Former student (and architect) Espie Dods remembered, “he built his life around [art] and carried through with it … what he said was part of him”.

For former Queensland state architect Malcolm Middleton: “He was the first person that awakened to me the importance of the relationship between buildings and the landscape. Sydney Uni was very deficient in acknowledging the discipline of landscape architecture … But Lloyd got it all together, the landscape and the buildings. And why you had to go and draw it, because you couldn’t understand how the building worked, how it had sat in that landscape, unless you could draw it.”

This book also traces Rees’s revelations and breakthroughs. Jenny More (another former student) recalled Rees speaking about “the movement of light, transient people, and the sublime”. She remembered him saying, “The older I get, the more wonder I have at the endlessness of it all”. Yet it was his belief that “a city is the greatest work of art possible”, with his carriage of influence and inspiration to those now responsible for these urban creations deftly conveyed.

Previously unpublished correspondence and artwork was made available by Alan Rees. A listing of brief biographies of the architects Wilson interviewed is useful, and the Afterword by Simon Weir (Perspective/s of Architecture: From Drawing to AI) introduces a slightly more academic tone, presumably to extend the experience of architects engaging with the book. An index would be a welcome addition.

The book reads like a labour of love, its discussion of what Rees achieved undulating throughout a biographical narrative that is highly readable. The longevity of his teaching relationship with Sydney University provides a base for the book’s chronological structure, perhaps similarly to the way that teaching economically underpinned his artistic achievements. Colour illustrations allow the words to be informed by the art and convey its transmutability to the broader landscapes and cities in which we live.

In its quiet reiteration of Rees’s vision, one that carried him through an at times difficult life, there is a real sense of a man whose significant achievements were never taken for granted. Alan Rees’s delivery of his memories, his loving evocation of “Dad”, brought a sense of Rees’s life force into the recent festival, even 37 years after his death.

Lloyd Rees and the Architects by Ross Wilson, AndAlso Books, 2025, $45.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence