The soft and quiet power of Australian literature needs public champions

Following the abrupt closure of Australian literary journal Meanjin after 85 years, Splinter journal editor Farrin Foster reflects on how literature’s quiet power makes it one of our least-valued art forms.

Last week, Australian culture was dealt a body blow when Melbourne University Publishing (MUP) announced it is ceasing publication of literary journal Meanjin. Literary journals are niche, but for the last 85 years, Meanjin has been a giant among its kind. This is something Foong Ling Kong, CEO of MUP, proudly highlighted in an email to Meanjin contributors last week.

“For 85 years, Meanjin has been a linchpin of the Australian literary landscape and the site of significant national conversations, launching the careers of so many.”

Then she dropped the other shoe: MUP was no longer willing to foot the bill to enrich the national conversation in this way, and would be shuttering the magazine entirely.

“MUP will cease publication of Meanjin after its final issue in December 2025 … The decision was made on purely financial grounds, the Board having found it no longer viable to produce the magazine ongoing.”

The shock and outrage across Australia’s literary community was immediate.

Early last year, I started working as the editor of Splinter – a new literary journal published by Writers SA, and while last week’s announcement was both chilling and saddening, it wasn’t as surprising as I would have liked it to be.

You might like

And that’s because literature, of all our chronically under-resourced art forms (hint: it’s all of them), is often the most under-resourced. It is easy to ignore because it doesn’t have many of the traits that traditionally help accrue political and social capital.

At Splinter, we are lucky to have support from our partners at Flinders University, the University of South Australia, and the University of Adelaide, and, significantly, from the state government via CreateSA. But even in our position of great privilege we are still under-resourced, and I’ve been exposed to the unique set of problems literature faces.

Evidence of this national problem can be seen in a microcosm here in SA. We like to look back with rose-coloured glasses to the Don Dunstan era, but it’s not fair nor true to say no-one has invested in the arts since the late ’60s. The Rann era’s contribution to our film industry can be seen at Adelaide Studios, established in 2011. Jay Weatherill fashioned himself as a Live Music Premier, launching the Music Development Office in 2014 and occasionally seen, tie-less and attempting to look carefree, standing in the vicinity of stages on which loud guitar-centric music was being played. Steven Marshall was, to the surprise of many, relatively arts-friendly and often seen front-row at Tarnanthi festival openings.

Our current Malinauskas Government (including Arts Minister Andrea Michaels, who I have spotted at literary events) has given us a long-awaited cultural policy, but despite an admirable defence of Adelaide Writers’ Week’s artistic independence in 2023, and namedropping American author Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation in his bid to get kids off social media, the Premier seems more likely to be seen at a LIV Golf tee-off than a poetry reading.

Literature’s low visibility is, on some level, unsurprising. It is hard to leverage glitzy outcomes from literary work; when literary superstars come to Adelaide, they don’t put the state’s name up in lights via gushy headlines like a visit from Cate Blanchett might (does). Outside of our wonderful but still occasional literary festivals like Writers Week, Weekend of Words, and Our Words, our core business (shudder) as literary artists doesn’t rate well on the neoliberal economic impact markers now entrenched in political discourse.

Subscribe for updates

We generate few “bed nights” in hotels, and don’t attract visitors to spend highly in our hospitality sector. Us literary types also lack the glamour and magnetism of, say, ballet or theatre, with splashy opening night events where politicians can see first-hand how many VIPs live for the performing arts. We also struggle to connect with philanthropists – another quality relished by politicians keen for anyone but the taxpayer to pick up the tab. But philanthropic support is also contingent upon visible impact, and literature’s impact is diffuse and often happens at the individual level: it is hard to sum up in a pitch deck or meeting.

"Outside of our wonderful literary festivals, our core business doesn’t rate well on the neoliberal economic impact markers now entrenched in political discourse. "

The problem, really, is that literature is often created and received in private, and that makes it harder for our capitalist society to assign value to it. But the essential intimacy of the artform is also an enormous part of its power – literature is transformative precisely because it speaks to us in our bedrooms, on our couches, sprawled in the Parklands, while we are soft, open conduits for ideas, voices, emotions, and experiences that can both broaden and validate our perspectives.

I believe the soft influence argument should be enough. But even on terms that a minister or policy boffin might care about, literature still kicks plenty of goals. It is a highly accessible and inclusive art form – a 2024 report says 80 per cent of Australians read or listened to a book in the year before the survey. By contrast, only 35 per cent of Australians attended the theatre (sorry theatre, ILY) in 2022. Also, yes, we cause money to move around – the domestic book industry sustains a market of about $1.7 billion and employs thousands of Australians.

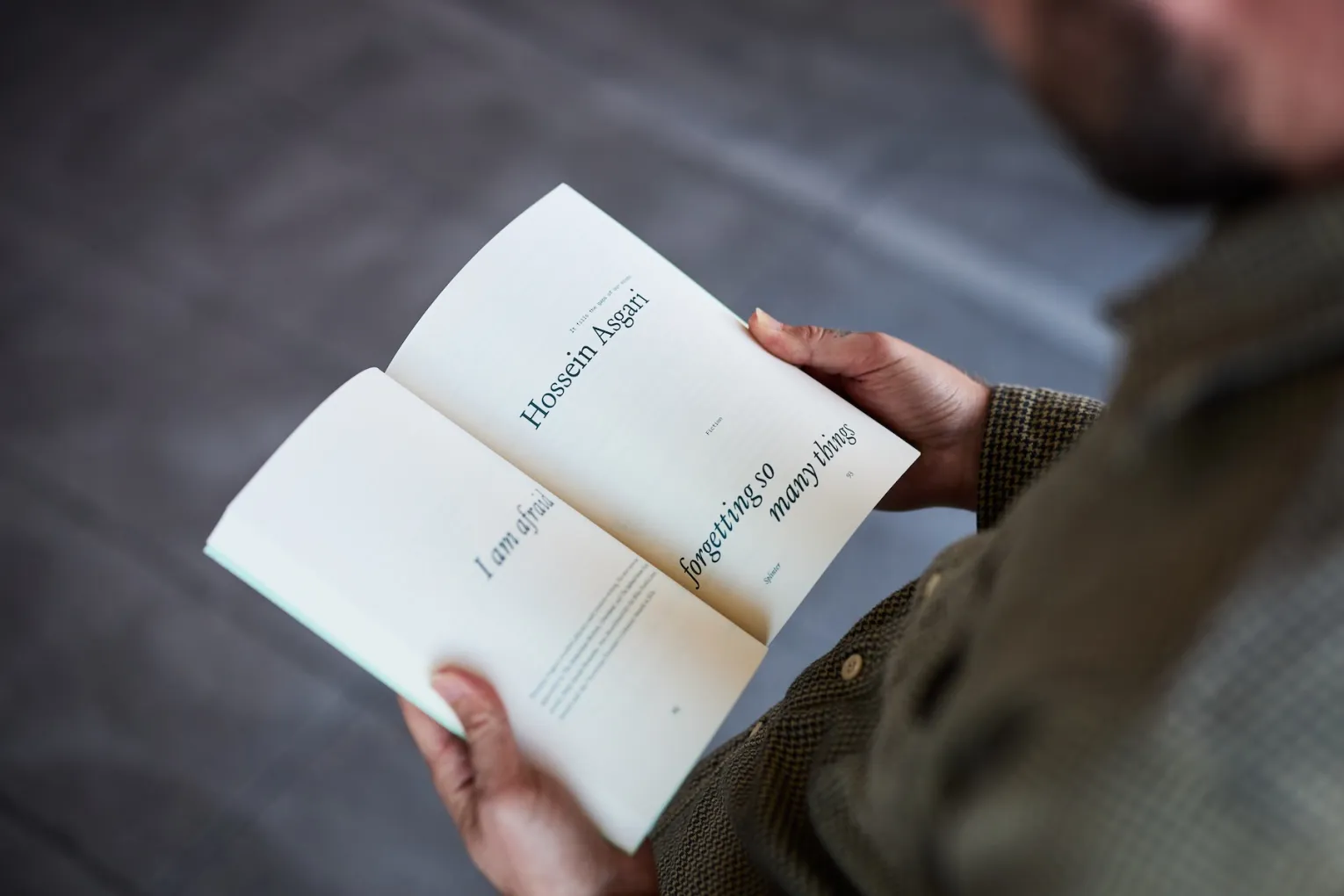

And, the state’s literary community is full of bright shining stars. Nobel Prize-winner JM Coetzee and bestseller Hannah Kent might have name recognition inside and outside the state, but we also have poetry legends like Jill Jones and Ali Cobby Eckermann, genre megastars like Sean Williams and Amy Matthews, and a next generation of literary superstars (if I were to bet, I’d put money on Hossein Asgari and Olivia de Zilva).

At Splinter, we have a mandate to publish at least 25 per cent South Australian writing. Fulfilling this requirement is, perhaps, the easiest part of my job. Every time we open submissions, writing of astounding depth, quality, and inventiveness pours in from around the state.

These writers deserve to be read, they deserve to be supported, and they – like the hundreds of thousands of readers here in SA – deserve to be celebrated as an essential part of our arts culture. We the people have a part to play in this – please buy books, support your local writers’ centre, turn up at live readings, keep flocking to Writers’ Week. Buy a literary journal, any literary journal, because these are where the vast majority of writers get their start.

But our leaders have to play their part too. The writers and readers of South Australia are a cultural force, but the word ‘literature’ doesn’t appear in our cultural strategy, and nor does ‘reading’ or ‘reader’ (‘books’ does score two mentions, while ‘writers’ crops up once).

I know we won’t ever have a Literature Premier – the artform simply doesn’t offer enough photo opportunities to demonstrate its healthy economic impact. But it would be nice if, in between lauding economic returns generated by the Adelaide Festival and Fringe, and giving the Adelaide Film Festival deserved praise for its delegation to Cannes, perhaps Malinauskas and Michaels could pause to tell us what they’ve been reading.

High profile acknowledgement from leaders is exactly the kind of thing that keeps institutional investment – like that just withdrawn from Meanjin by MUP – flowing.

It’s also the kind of thing that reminds us all – writers, readers, and funders alike – that staying home to read or write is just as much a cultural contribution as heading out to see a show.

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence