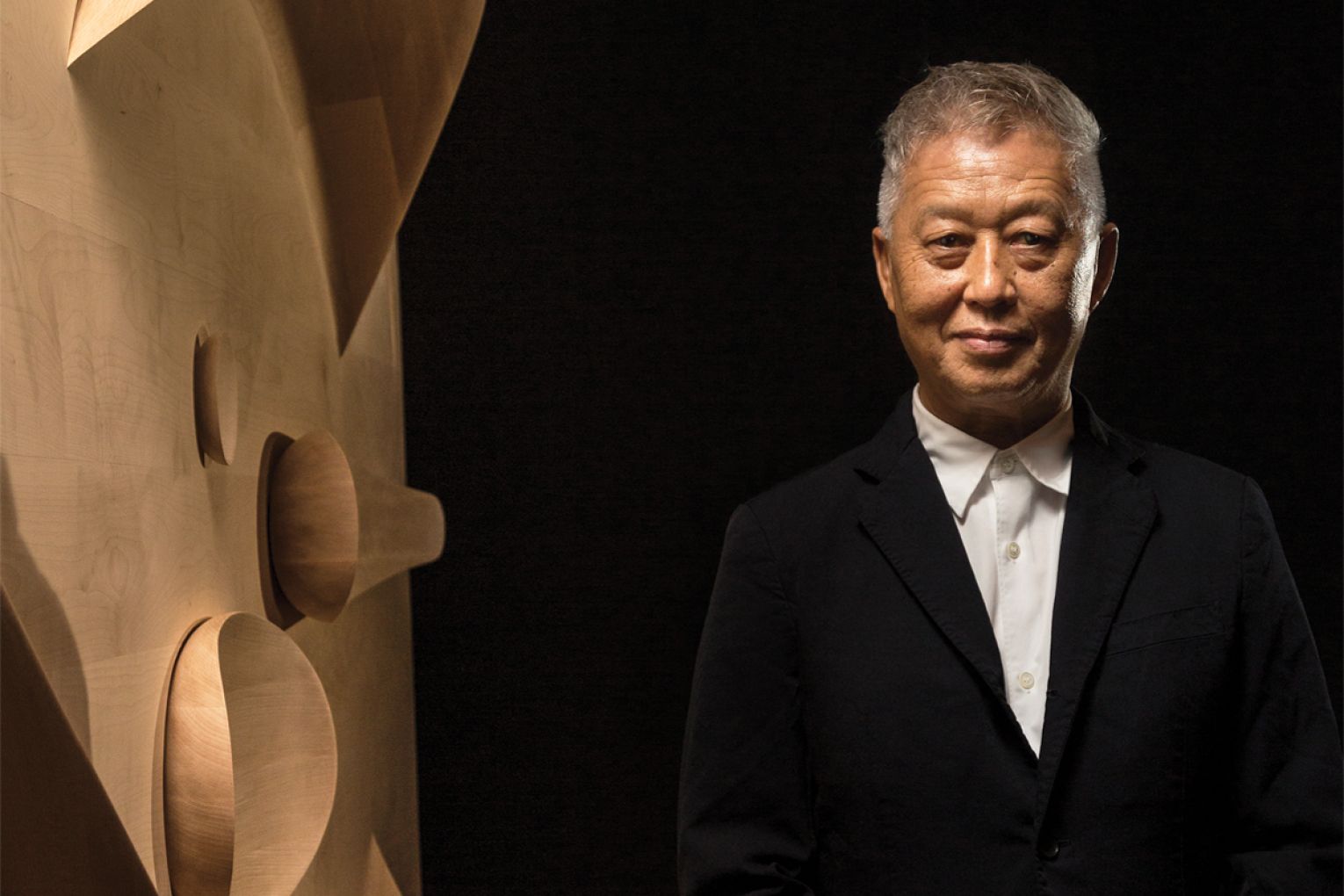

The legacy of Khai Liew

A gifted craftsman, Khai Liew left an endearing legacy of design and collaboration after his passing in 2023.

There’s a story that Cheong Liew recalls about his late brother Khai which beautifully illustrates the innate gift and grit of the award-winning furniture designer, collector and conservator.

Cheong says in the early days, Khai would spend hours scouring second hand shops, even the Wingfield dump, searching for unique furniture pieces which he would meticulously bring back to life.

“I remember he went to the dump to pick up a chair, polished it up and it sold for more than $10,000. He knew what he was picking,” Cheong says.

“He just had a really good eye. I think he was gifted, it’s not something you can study.”

That gift of discovering discarded, yet valuable, pieces and knowing how to restore them remained at the heart of Khai’s astounding career as a self-taught craftsman and designer.

“I remember he started off buying a couple of old chairs and an old table and instead of paying $600 for something he’d pay $120, and he’d clean it up,” says Cheong, who also rose to the top of his field as a self-taught chef. “Khai wasn’t thinking about antiques at first, just usable pieces.”

Khai’s death in December 2023 was felt deeply throughout Australia’s artistic and design communities, where he had been a visionary and mentor for decades.

The 71-year-old passed away peacefully with his adored sons Jian, now 37, and Remi, 35, by his side after a short battle with lung cancer.

The boys’ mother and Khai’s former wife Suzanne Kellett describes the designer as “the eternal optimist, embracing life and his work with passion and enthusiasm”.

“He was a free spirit, a loving dad to his sons, a loyal and generous friend and a person who was a great source of inspiration to many,” Suzanne says. “I always thought of him as being two steps ahead of everyone else.

“Khai’s large and loving family meant the world to him.”

Looking back, Cheong says Khai was always creative, a talent no doubt inherited from their father who designed the family home in Malaysia, a Japanese-style house that was filled with Danish furniture.

The family grew up on a large poultry and vegetable farm and Khai was number five of nine siblings to mother Cheong Sow Keng and father Liew Wan Thye.

“Our father was a draftsman for an English construction company designing either roads, bridges, or buildings,” Cheong says.

You might like

The family was forced to flee Malaysia during the May Race Riots of 1969, eventually immigrating to Australia in 1971.

Khai attended Sacred Heart College as a boarder, while Cheong ended up studying in Melbourne, but he recalls visiting Khai in Adelaide and marvelling at his younger brother’s ease with people and his popularity.

“In those days Asian students hung around with each other, but when I came to Adelaide to visit Khai he’s got Italian friends, Polish friends, so many different friends and I thought, ‘This is great, at last I am getting to know the Australian community’,” Cheong says.

“That’s what attracted me to moving to Adelaide and I followed him here.”

Khai ended up studying economics at Flinders University, while Cheong started engineering, and the brothers lived together in a variety of student share houses around the Fullarton and Highgate areas or “Liewville as we called it”, Cheong laughs.

“Khai was always the leader of the group,” he says. “He would always organise things and manage things. I’m older than him and he used to manage me.

“He was so ordered and organised. He and I were chalk and cheese, really.”

While he was studying, Khai began working as a waiter at a Greek restaurant in the city called The Illiad. He also organised for Cheong to work in the kitchen there, igniting a culinary career that would see Cheong go on to global success and heading up prestigious Adelaide restaurants including Neddy’s and The Grange at the Hilton Hotel.

“He was a waiter, and he was a super waiter. I couldn’t believe it. In those days, the wages were only about 60 or 70 bucks a week and he was making two to three hundred in tips,” says Cheong.

“He was so clicked on, you know, whoever wants a table he’d say, ‘no problem, I’ll get another tabletop’. I think it’s his smile and his approach.”

While he was waiting tables, Khai was also cultivating his passion for furniture and design.

The self-taught craftsman would read books and devour any information he could about furniture design, particularly the history of Australian furniture and historic furniture in the Biedermeier/Barossa tradition.

By the 1980s, Khai opened his own furniture store Augusta Antiques in Norwood, on the same site where his Magill Road studio now stands. He then gradually moved out of antiques and began specialising in 1950s Scandinavian pieces.

But it was in 1996 that the humble and quietly spoken designer got his first big break when Art Gallery of South Australia’s then-director Ron Radford commissioned Khai to create a series of benches for gallery visitors.

Rebecca Evans, the Art Gallery of SA’s current curator of decorative arts, worked closely with Khai on his bench commission.

“His masterful work has long been characterised by deceptively simple shapes, employing ideas of rhythm, musicality and repetition in form. Liew carefully selected his materials and employed the remarkable skill of a team of expert cabinetmakers to realise his vision for contemporary furniture design,” Rebecca says.

As well as his exceptional talent, it was the designer’s open-hearted willingness to collaborate with others, to bring peers along on his creative journey, as well as mentor newcomers, that perhaps remain his most endearing legacy.

“I miss him dearly,” Rebecca says. “Khai supported many generations of decorative arts curators at the Art Gallery of South Australia. I value and appreciate his generosity in sharing his knowledge of my field. He was never pushy, always generous and had impeccable connoisseurship.”

Cheong remembers his brother being “so thrilled” about the bench commission and says after that, “he was on his way”.

Working under the brand Khai Liew Design, the gifted artisan and his small team of dedicated craftsmen began creating beautiful one-off design commissions, using natural materials such as wood, leather, stone, grass and linen.

The designer’s first solo exhibition, Long Weekend, was held at JamFactory in 2001 and his follow-up show, Tiersmen to Linefold, an exhibition of 14 furniture pieces, took place in 2007.

As well as private commissions, Khai’s design studio contributed to exhibitions both in Australia and globally with his work featured at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Design Museum, both in London, as well as the Triennale di Milano in Milan.

In Australia, Khai’s pieces form part of the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Australia, Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, the Art Gallery of Western Australia and the Art Gallery of South Australia.

The awards and accolades were many including in 2010 when Khai was awarded the South Australian of the Year Arts Award, in 2016 he was inducted into the Design Institute of Australia Hall of Fame and in 2017 he received the Design Institute of Australia Design Icon award. Khai was also commissioned to contribute to the interiors of the luxurious Southern Ocean Lodge on Kangaroo Island.

Subscribe for updates

Art Gallery of SA director Jason Smith says he only met Khai once but adds, “His work and reputation were far-reaching and from my first encounter with his furniture and objects I was a devotee.”

“The deceptively simple, sinuous line or precise geometry and joinery in Khai’s work reveals not only his technical mastery of traditional and innovative woodworking, but a profound and poetic understanding of his materials,” Jason says.

The Gallery has 16 works by Khai in the permanent collection, including the more recent acquisition of a love seat titled Alice and friend in Wonderland, 2020, which Rebecca Evans cites as her favourite Khai Liew piece.

“This love seat includes a simple bench seat with splayed legs, the back rests, like two-rabbit ears sits surrounded by a dramatic arch,” she says. “The form of this chair plays with perspective; from the front the chair looks simple, even flattened in form, yet from the back a curvaceous behind is revealed – a subtle playfulness.

“This chair comes from a body of work produced by Liew for the Sydney-based businesswoman and philanthropist Judith Neilsen’s inner-city home. Taking inspiration from her then young grandchildren, many of the works employ an element of child-like playfulness and whimsy channelling the worldview of young children. This series also included a sunflower chair, penguin side table and Shaun the Sheep lounge chair.”

Cheong says part of Khai’s nature was to share the spotlight and creative ideas with others. “This collaboration also helps to encourage our inspiration and innovation with someone who may be working in a different area. That’s how you learn more from each other.”

Cheong says his brother’s passion and eye for detail were at the heart of his creative success.

“I think that’s what happens when you dive into something that you are so passionate about, and Khai would research the wood, the fabric, and how he’s going to design it,” he says. “His speciality was the joint, which is a Chinese style of joining, so you don’t need any nails.”

As he talks to SALIFE, the now-retired Cheong shows off his bookshelf bursting with cookbooks.

“I’ve got all these books, and there’s more upstairs, and Khai was the same with his books,’ he says. “He had so many books from so many different countries, especially Japan, and not only furniture but dress making as well, so he knew all about fabric.

“He’d research something and then go and find it. We were almost doing the same thing except he was doing it with furniture, and I was doing it with food.

“We both always believed that if you want to learn something you have to find out about it yourself, which is so much more fun than going to school and getting all this information, because for me it’s a lot of trial and error, and I think it was the same for Khai.”

So, did the brothers take time to reflect on their respective success and rise to fame?

“When it comes to making money, Khai used to say, ‘Cheong I’m like you, I make money with this hand and give out with this hand’,” he says.

“We never accumulated much money, but we are happy with what we are doing.

“I always really appreciated his work, and I used to say, ‘I love your sunflower chair, and it takes a great imagination to design the Shaun the Sheep chair’.

“He was not just a furniture designer, he was an absolute, true artist, in his own form, because you are really building, doing all the groundwork.”

Khai’s passing marks the end of an era for Adelaide’s creative community, and for his family, friends and colleagues it is still difficult to come to terms with the enormous loss of their father, friend, mentor and mate.

Cheong says he visited his younger brother in hospital in the last few weeks of Khai’s life.

“I miss his smile,” he says. “He was always someone who cheered me on as well, supported me, and appreciated what I was doing. Of all the siblings I’d be the one who was closest to him.

“I think his legacy is that he was a great Australian artist. He could have been a painter, or anything, but it was furniture.

“I think about him now when I’m cooking a curry. He loved my vindaloo curry.”

Suzanne Kellett says Khai “was not ready to leave this world”.

“He loved life and had an abundance of creative energy and unfinished business,” she says. “He was so proud of the team he left behind in his workshop.”

A spokesperson for Khai Liew Design told SALIFE: “We are in the process of carefully working to honour what Khai built, not only the furniture and designs, but the studio, community, archives, and the ideas and spirit that shaped them. His work was never just about objects; it was about values and the way design could shape how people live. Our focus is to ensure his vision is preserved and continued in the right way, so that his life’s work remains accessible, understood, and enduring for future generations.”

This article first appeared in the October 2025 issue of SALIFE magazine.