A modernist maelstrom or thoughtful deep dive into the interior worlds of women?

Although less edgy than its ‘dangerous’ title suggests, the Art Gallery of South Australia’s winter drawcard offers a mood of introspection — and some long-overdue recognition — that remains groundbreaking.

Dangerously modern: Australian women artists in Europe 1890-1940 delivers that rare experience, a groundbreaking and thought-provoking deep dive into a relatively neglected aspect of Australian art. As the ticketed highlight of the Art Gallery of South Australia’s winter program, the exhibition is competing for interstate visitation with the big guns of French Impressionism in Melbourne and Cezanne to Giacometti at the National Gallery in Canberra. Countering usual expectations of international trumping the local, in its ambition of extending our understanding of previously under-examined aspects of the emergence of Australian modernism, Dangerously modern is arguably a more essential viewing experience than the blockbuster offerings from abroad. We surely need these opportunities to fill in the gaps in our own national art history and especially to redress the double neglect of women artists and of the art they made beyond these shores.

But don’t go to the exhibition from a sense of duty — go for the sheer pleasure of it. Dangerously modern is the full sensual overload, a feast of beautiful, thoughtfully displayed art which emanates a palpable female aesthetic synergy.

The 50 women artists in Dangerously modern were intrepid travellers, voyaging from the antipodes to the world’s great cosmopolitan cities of Paris and London. Some lived for periods in rural artist colonies and others made sorties to discover the exoticism of Morocco and North Africa. Most sought to escape the narrow confines of Australian society, to embrace a modern, liberated lifestyle and to make art with the supportive fellowship of like-minded artists. Amongst this cohort some, including Agnes Goodsir, Bessie Davidson, Stella Bowen and Anne Dangar, became permanent expatriates while most returned to Australia and New Zealand, bringing with them the influences of their exposure to European developments in modern art.

There is a broad sweep to this exhibition of 220 works of art, firstly in its embrace of artistic developments across 50 years — from Edwardian England and the Parisian salons to cubist-influenced abstraction of the 1930s, and secondly, in its exploration of the intersecting lives of the artists. The exhibition came about when co-presenters AGSA and the Art Gallery of NSW decided to combine two separate but similar exhibition proposals being worked on by their respective curators, namely Elle Freak and Tracey Lock (AGSA), and Wayne Tunnicliffe (AGNSW). Grafting the two proposals may be responsible for some loss of coherence, with notions of artistic modernity slipping in an out of focus as one moves through the exhibition.

You might like

Even after viewing Dangerously modern on several occasions and reading most of the substantial catalogue, the choice of this title to market the exhibition remains perplexing in terms of its mismatch with the actual art. Granted it is a huge somewhat unwieldly exhibition, difficult to encapsulate in a snappy title. The overwhelming impression, for this viewer at least, is of a mildly modern, largely figurative interpretation of modern art, eschewing the iconoclastic extremes of fauvism, cubism and constructivism. Rather than the maelstrom of modernity, we encounter a mood of introspection, an interior world of women, their lovers and their domestic living spaces.

"Rather than the maelstrom of modernity, we encounter a mood of introspection, an interior world of women, their lovers and their domestic living spaces."

Freak has written in her catalogue essay, ‘Inner Space’, of a “quietly subversive modernism” that was “coded with sapphic symbolism”. This reflects a key theme driving the exhibition, namely how art may be seen as an expression of each artist’s inner life in response to their experiences of modernity. In turn, this has led to a grouping of art in a sequence of rooms, according to five themes, ‘Search and solitude’, ‘Radiance and rupture’, ‘Loss and renewal’, ‘Awakening’, and ‘Resolve’, with wall texts which set out to explain each grouping. There is a degree of interpretative license in this grouping of art according to psychological criteria that risks imposing a curatorial viewpoint rather than illuminating the art. Conversely, it may be argued that this original approach has the potential to offer new insights for both art historians and the wider public interested in women’s art.

Subscribe for updates

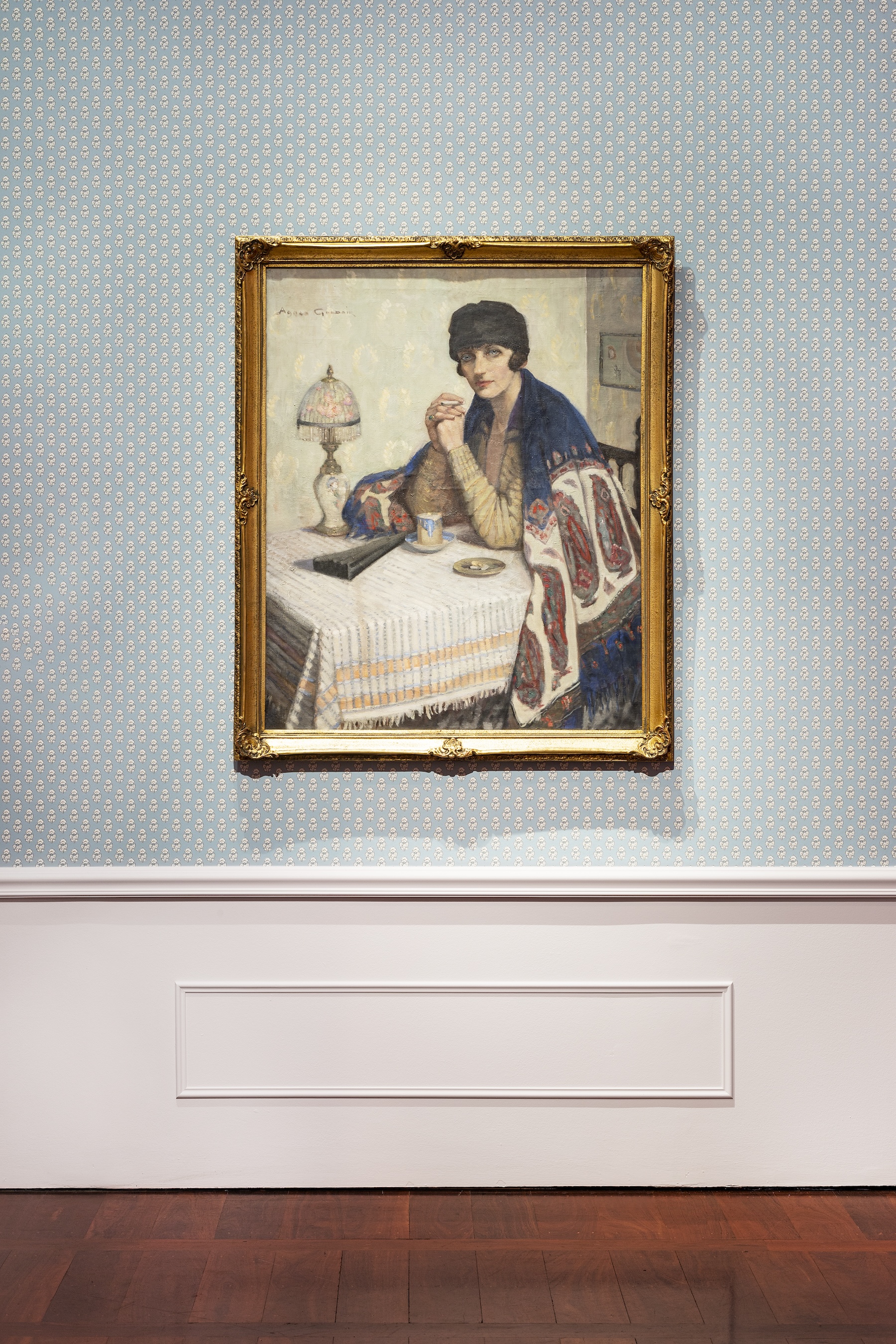

The entrance to Dangerously modern, via AGSA’s downstairs temporary exhibition galleries, is designed to instil a sense of departure from everyday reality, as we pass through a portal lined with white drapes. This funnels the visitor into an intimate enclosed space, decorated with powder blue wallpaper and housing cases of charming Edwardian miniatures. Immediately our expectations of encountering ‘dangerous’ art are disrupted. Until, that is, we turn to the adjacent wall to encounter a startling painting of a pastel-toned nude, Girl sitting on a bed, 1917-18, by New Zealand artist, Edith Collier. There is a modern freshness to the frank portrayal of the young woman’s relaxed, introspective nudity, painted with a loose brushwork which contrasts with the finesse of the miniatures. The sting in the tail, emphasising the unlikely ‘dangerous’ modernity of Collier’s painting, lies in the accompanying text where we learn that on her return to New Zealand her father was so hostile to her art that he burnt nearly all her paintings.

Throughout the ensuing gallery spaces there is a loose chronological progression, with highlights including the strategic placement of riveting paintings by Agnes Goodsir, Bessie Davidson, Hilda Rix Nicholas, Grace Crowley and Stella Bowen. These artists portray women possessing a confident, cosmopolitan panache and a self-contained strength. Their portraits preside over the gallery spaces to imbue each area with a palpable female presence. However, it is deflating to depart the exhibition with the final impression of Nora Heysen’s defiant realism in her portrayal of dejection and failure, Down and out in London, 1937.

While the NGV has reportedly chosen to go over the top with a luxurious palatial setting for its Impressionism exhibition, AGSA’s exhibition designers, Grieve Gillett Architects, have created an ambience that conjures psychological and emotional states corresponding to room themes, progressing through blue, mauve, pink, and orange paint tones for the walls with occasional wallpaper highlights. Overall, this design works effectively to create moods in each area that complement the art. However, both the curators and designers tread a fine line between enhancing the art and manipulating a desired response from viewers.

This is most obvious in the heavy-handed staging of the ‘Interiors’ room which houses luminous paintings of interiors by Bessie Davidson, Agnes Goodsir, Margaret Preston and Stella Bowen. The design decision to drape the room in white and to insert the corny prop of a backlit window has the perverse effect of distracting from the paintings rather than heightening our viewing experience. Similarly, the towering triangular wall display of cubist-influenced art may work as spectacle but compromises viewing of the subtleties of Grace Crowley’s paintings.

These critical reservations aside, Dangerously modern deserves acclaim as a landmark artistically significant and hugely enjoyable achievement. It is a must-see event, and possibly a once-in-a-lifetime chance to view such a substantial collection of so much rarely seen art by so many wonderful women artists.

Dangerously Modern: Australian women artists in Europe 1890-1940 continues at the Art Gallery of South Australia until September 7

Free to share

This article may be shared online or in print under a Creative Commons licence