Inside the painstaking $6.2m conservation of Adelaide Town Hall

For two years, the Adelaide Town Hall has been hidden by scaffolding as a conservation of its façade took place. InDaily takes a look at the painstaking process, from carving 60 stones by hand to importing gold leaf from Italy.

The central body of Adelaide Town Hall was built between 1863 and 1866, Swanbury Penglase director Andrew Klenke begins as he delves into the painstaking restoration of one of the state’s most important buildings.

“The amazing thing about the Town Hall is, I’ve looked at a lot of heritage places over the years, but I think in terms of conclusions, I’d have to say that the Town Hall’s probably one of the most significant,” Klenke, who leads his firm’s heritage conservation and adaptive reuse team, says.

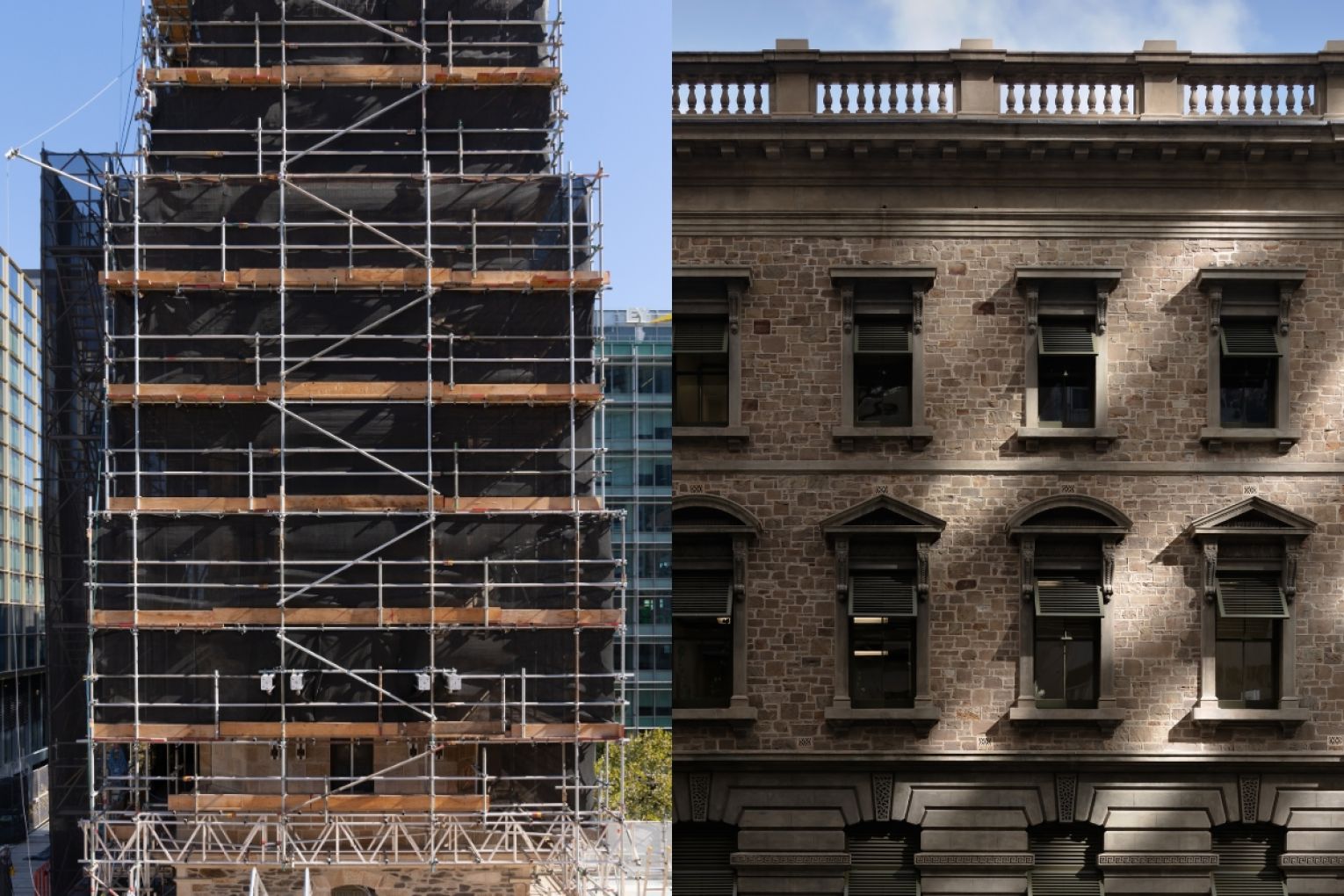

Swanbury Penglase was the architecture firm involved in a comprehensive, two-year-long, $6.2 million conservation of the Town Hall’s façade, alongside Australian contracting company Duratec.

Duratec senior project manager James Biven, who oversaw the Adelaide Town Hall façade conservation, says it was the first major restoration of the building since it was built from Tea Tree Gully freestone and Dry Creek bluestone.

Biven emphasises the importance of preserving all of the Adelaide Town Hall’s original fabric, particularly as it is a State Heritage-listed building.

“We drilled lots of small holes and injected glue behind the render to hold the original fabric back on – it’s a lot more time-consuming and costly, but it’s a requirement of State Heritage, of the Burra Charter, which is the overriding set of principles governing heritage restoration,” he says.

“Council is actually really nice to work for. They put a lot of pride and effort into their heritage buildings, and they did things properly, which was really refreshing.”

The works were staged around Town Hall events such as music performances, with the majority of scaffolding erected at night for safety reasons.

You might like

Biven tells InDaily that there were some sections of the structure that were in a very poor state.

This included a lot of discolouration, and areas where cast iron metal had started to rust and expand due to water getting in, damaging stones and causing them to crack.

“There were sections getting very close to falling off. There was a lot of mould. There were some small plants growing on it,” he says.

“We repointed the entire tower plus a bunch of other areas in the building to make it watertight and protect it.”

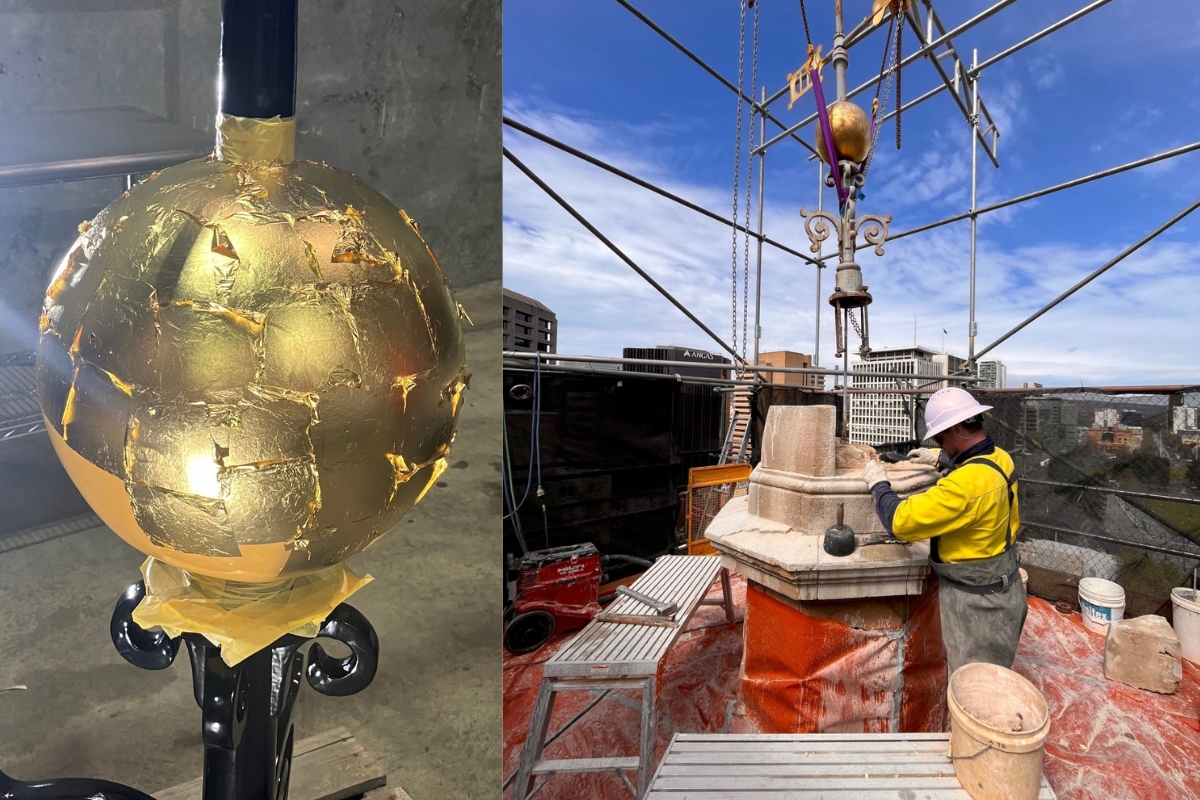

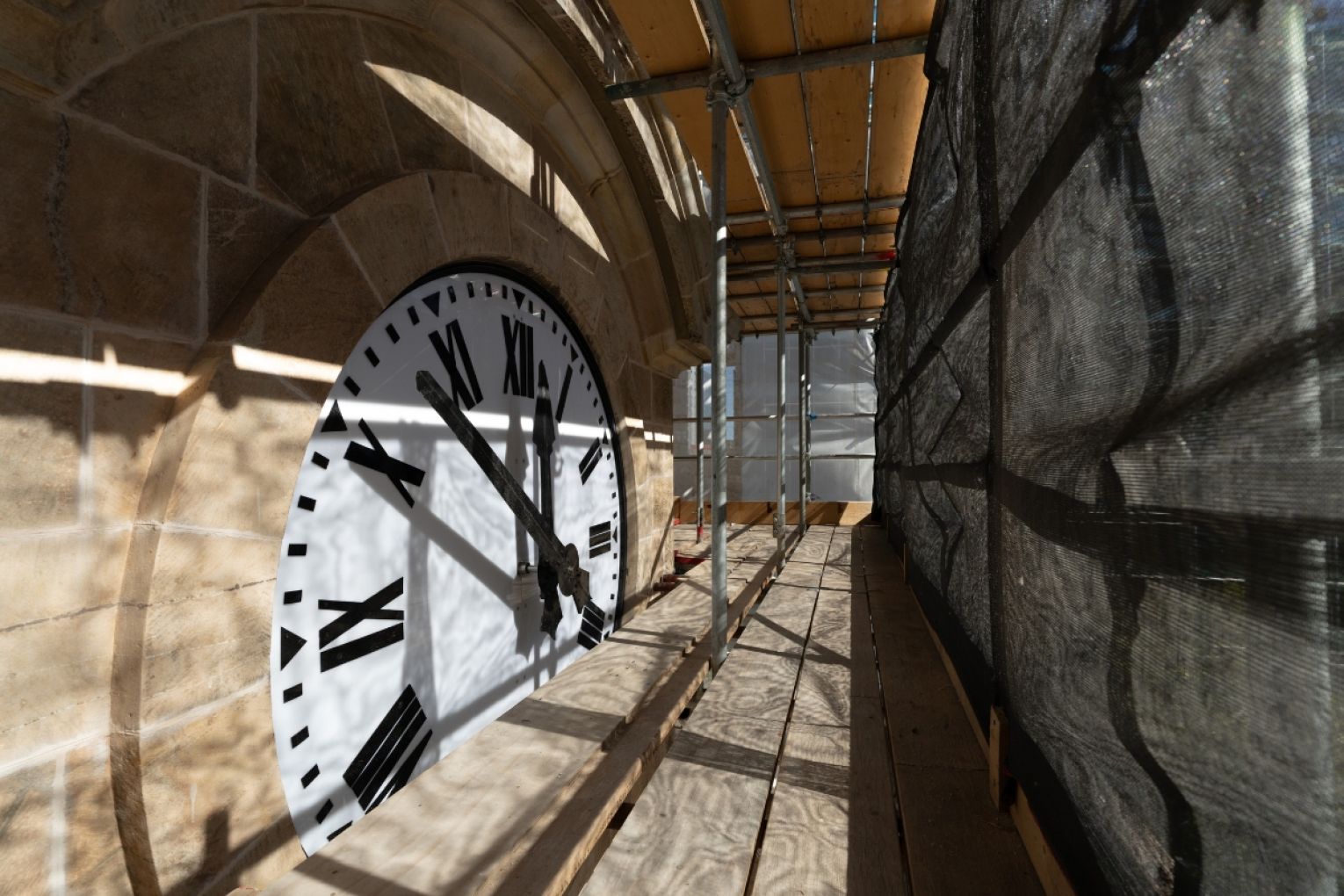

The project involved cleaning the entire building, consolidating the render, carving 60 new stones by hand, and demolishing and rebuilding the lantern on top of the cupola.

“We engaged a stone scientist who’s based in the Adelaide Hills, and they analysed the existing stone and then they worked out which quarries around Australia are operating and produce stones the most similar in colour, density, texture and size,” Biven says.

“We found a few stones tucked on the back of the tower where craftsmen from over 100 years ago have carved their names into it, leaving a history of who worked on it before – that was pretty cool.”

They also regilded the cast iron weathervane on top of the building’s dome with gold leaf imported from Florence and put in lead flashings over sections that had water damage for protection.

Klenke says the Town Hall was constructed on The Corporation Acre, the original land division of Adelaide.

Surrounding buildings were built over the next 15 years and originally leased to private businesses, before being gradually taken over by the Adelaide City Council since the 1950s.

“The Town Hall that we see today is actually fairly complicated because it’s made up of a whole bunch of different structures, including the section to the south of the Town Hall, which was originally the Prince Alfred Hotel,” he says.

Stay informed, daily

The Town Hall hasn’t always been primarily home to staid politicians in suits, with some wild and wonderful events happening on site over the years.

Klenke says that when the building was nearing completion in November 1865, 30 of South Australia’s most prominent men gathered for a topping-out ceremony on the slightly unsteady scaffolding.

“One fellow had a bit too much sherry, and he actually climbed on top of the finial and spun around,” he says.

There was also a riot outside the Adelaide Town Hall in March 1904 during a lecture by Reverend John Alexander Dowie, who styled himself as “Elijah the Restorer”.

Born in South Australia, Dowie had established a religious movement while living in the United States and had returned to his birthplace while on a global tour to convert the world.

An angry crowd of 10,000 to 15,000 people objecting to his push for the new movement were prevented from entering the Town Hall to stop Dowie speaking, leading to a chaotic riot as both police and the crowds brawled, with one police officer stabbed in the process.

“There were broken windows, trams were damaged and all sorts of things,” Klenke says.

And then, there was an appearance by the famous British racing car driver Donald Campbell.

“The one I love is, everybody knows about the arrival of The Beatles there in 1964 – people have probably forgotten that Donald Campbell, who had broken the land speed record three months ago at Lake Eyre in the Blue Bird, actually ended up driving down King William Street and had a civic reception at the Town Hall,” Klenke says.

Biven and Klenke both say they felt privileged and honoured to work on a heritage building such as the Adelaide Town Hall.

“I like the challenges of heritage buildings, which are different from new builds or extensions and renovations,” Biven says.

“Working with the trades is pretty fun because there are some really specialised trades who are super knowledgeable in their specific area, and just learning from them is really cool.

“I think it should be another 50 years or so before any major works are required.”