SA Holocaust museum founder tells story of escaping execution

SA’s Holocaust museum is receiving $500,000 in the wake of the Bondi terror attack. InDaily shares the story of the museum’s peace-seeking founder who narrowly escaped being shot by fascists in Hungary. His neighbours were selected for execution instead.

The State Government this week announced it was doubling funding for the Adelaide Holocaust Museum and Andrew Steiner Education Centre in Wakefield Street from $242,360 to $500,000. In the wake of attacks on the Jewish community in Bondi, the money will be spent on education about the Holocaust and on tackling antisemitism in an expanded teaching program.

Founder Andrew Steiner OAM welcomed the funding, saying the “horrendous tragedy” will be a “turning point, a wake-up call to redouble our efforts against any kind of differentiation, any kind of misbehaviour against any other group”.

A few weeks ago, the centre’s founder spoke with InDaily about winning a global peace prize.

Holocaust survivor Andrew Steiner OAM describes the immense honour and privilege he feels at being awarded the inaugural Éva Fahidi Award last month, adding that at 92 years of age, he felt travelling to Budapest to receive the accolade in person was “too demanding”.

Named after prominent Hungarian Holocaust survivor, Holocaust educator and dancer Éva Fahidi, the prestigious international prize recognises extraordinary individuals who, “through their personal example of their work, inspire and support the next generation to live in an inclusive, compassionate, and caring society”.

Andrew, who was the driving force behind the establishment of the Adelaide Holocaust Museum and Andrew Steiner Education Centre (AHMSEC) in 2020, says the museum will pay homage to Éva by displaying the award that arrived in the mail this week alongside a biography of her life.

Although Andrew never met Éva, he describes her as a “wonderful human being exercising her power of one”.

“So, she’ll be here, firstly, by paying homage to her, and secondly, equally importantly, to inspire our visitors and to emphasise this inner great power of one, which all of us possess,” he says.

“‘Do they always come up to the surface?’, ‘Are they always utilised?’, I wouldn’t say always, and it’s so much easier to just say, ‘Yes’, just to agree irrespective of the consequences.

“That is partly why we are here today in this situation all around the world – hatred, increasing antisemitism, instability, very, very selfish, tyrannical governments, human rights trampled upon, and that’s why this institution, this museum, and our education program towards a better, more just, more compassionate world, is key for our future.”

You might like

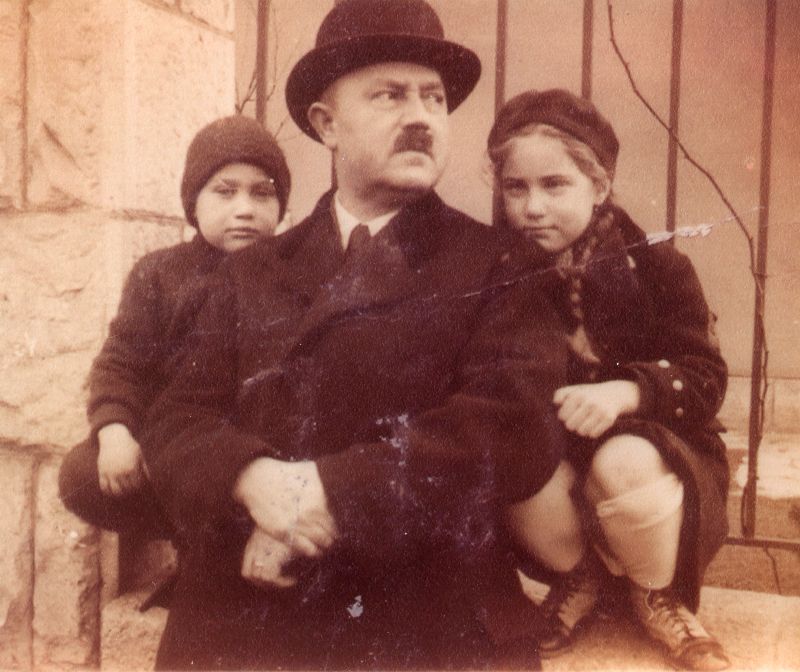

Andrew was born in 1933 into an affluent Jewish family in Budapest, describing it as an “extraordinary, beautiful city” and “the metropolis of Europe”.

On his maternal side, his family descended from a long line of learned rabbis and scholars, but religious practice in his family had become somewhat diluted.

Andrew and his family spoke Hungarian at home, with Andrew emphasising their patriotic loyalty to Hungary.

“The emphasis needs to be on our absolute allegiance and love for Hungary, and of course, later on, it didn’t make a scrap of difference and neighbours with whom we have had good, cordial relationships turned against us and really did their utmost to see us killed,” he says.

Andrew’s comfortable upbringing all changed when the German Nazis and their collaborators began their industrial-scale murder of six million Jews across Europe.

In October 1944, Nazi Germany orchestrated a coup and installed a new government in Hungary dominated by the fascist Arrow Cross party.

Of the 825,000 Jews who called Hungary home before World War II – including 200,000 who resided in Budapest – 565,000 were killed in the Holocaust.

Following the occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany in 1944, Andrew spent most of his childhood in hiding, along with his sister and parents.

In Andrew’s immediate family, 12 of his relatives were murdered, including his aunt, her husband and his two cousins.

“They (the Arrow Cross party) immediately unleashed their hatred and were more sadistic than the German Nazis. So, we were there, hands up, lined up to be executed,” Andrew says.

Andrew says that there is “no explanation” for how he survived, saying that an Arrow Cross paramilitary had lined up his family outside their house, ready to be executed.

A random soldier suddenly appeared, and the paramilitary turned their attention to another family, who were murdered on the spot.

“This is not the only instance where a split second made the difference between survival and perishing,” Andrew says.

Stay informed, daily

“And of course, that was a failed execution. People across the road, an entire household, 14 people, murdered on the spot. ‘Why did they have to die?’, ‘Why did we survive?’ – there are no answers.

“When we went back to our villa after the war, the next-door neighbour looked at us, kept shaking his head, and then, after a while, he said, ‘This is so terrible, what a shame – more of you came back than were taken away’. So, how’s that for a friendly, neighbourly welcome?”

The Steiner family managed to secure permits to come to Adelaide prior to World War II, but became stranded in 1939 and only managed to make it to Adelaide in 1948.

Andrew describes the incredible culture shock he felt when arriving in Adelaide after the War in 1948, where food was bland, and it was frowned upon to speak a foreign language.

“Adelaide was really, totally parochial, isolated and everything different, and we kind of felt that we were on another planet,” he says.

“What we have become is a multicultural, largely homogeneous society, which is, of course, currently experiencing very severe cracks.

“We have a lot of work to do to make sure that we maintain the respect of other people’s background, other people’s religion, of other people’s sex preferences, whatever it is, it’s their right to exercise that.”

After moving to Adelaide, Andrew began his career as an artist, with a focus on woodcarving and sculpture.

It was through his artwork that Andrew managed to come to terms with his experience as a Holocaust survivor.

“Each of us has to deal with that trauma, that experience in our own personal way. Nobody can ever understand what that person has gone through, what that person is carrying as part of their being,” he says.

Andrew has been educating South Australians about the Holocaust since the 1990s and was a driving force behind the establishment of the Adelaide Holocaust museum in 2020, which is housed in Fennescey House – a property owned by the Catholic church next to Saint Francis Xavier’s Cathedral.

Now at 92 years old, Andrew lives in Adelaide near his three adult children, his six grandchildren and his nieces and nephews.

Andrew says his next dream is to advocate for a fairer, more just, more compassionate society, saying that, sadly, the world has become very reminiscent of the 1930s.

“Compassion has no limitation. Compassion is treating everybody the way you yourself wish to be treated,” he says.

“Compassion is not doing anything to anybody that you would not wish to have happen to yourself – that’s compassion

“And that breaches and overcomes all the differences because, fundamentally, we’re so similar. Differences are infinitesimally small. So, that’s the reality.”

More State Government funding approved by Education Minister Blair Boyer would also be used at the centre to employ a senior educator, broaden access to its program for regional and disadvantaged communities, and enhance and expand partnerships with institutions such as Flinders University and the Children’s Rights Centre of South Australia.