SA ex-prisoner’s call on drugs as user numbers surge in courts

More than 70 per cent of SA prisoners are reporting illicit drug use before their convictions. An advocate says: “When you see yourself as a criminal drug addict, it’s very hard to imagine yourself doing anything different.” One ex-prisoner shares his story.

Adelaide’s Merlin Faber was sentenced to four years at Cadell Training Centre on drug trafficking charges in 2017. Despite now turning his life around and completing a double degree in law and journalism, the 31-year-old says the post-release drug counselling courses he attended were “a waste of time”.

Following his release after serving seven months, Faber completed the Home Detention Integrated Support Services Program (HISSP) funded by the Department of Correctional Services.

He said the sessions were “limited to eight to 10 sessions” where counsellors would “repeat the most fundamental things about substance abuse and drug avoidance”.

“For that program to be effective, you would only be hitting an incredibly small margin of people who are on drugs who would benefit,” he said.

Most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data showed the number of total prisoners in SA increased by 12 per cent in the 12 months to June 2024, and more than 70 per cent reported illicit drug use prior to conviction.

SA currently has an estimated 3400 prisoners in custody and data showed one in three offenders returned to prison after their release.

Faber, who has now completed a double degree in law and journalism at the University of South Australia, criticised the ineffectiveness of counselling and “fruitless” conversations that “ignored generational cycles of trauma and socioeconomic disadvantages”.

“I was genuinely interested (to see) if they had something relevant to say that was from a therapy standpoint,” he said.

Faber believed a stronger support program, including ensuring prisoners were properly housed and supported with basic educational support, would make an impact.

You might like

He pointed to the “huge issue” of literacy rates in SA prisons that made the Work Ready, Release Ready (WRRR) program difficult for most released prisoners.

“If you don’t know how to read, how are you going to be able to find a job with an ankle bracelet that pays anywhere near sustainable wage,” he said.

For some prisoners it would be “easier to commit a crime and go back to jail” than find housing, he said, saying a more holistic approach to post-release programs would further reduce recidivism rates in the state.

“Intervention has to fit in with that ecology of good health where drug intervention, access to education, housing and upskilling need to be functioning in a network for it to be effective,” he said.

“When they don’t communicate and don’t collaborate, it’s just ping pong with more paddles.”

SA also operates a Treatment Intervention Court providing programs for people charged with offences who have mental health or mental impairment and/or illicit drug use problems.

It operates from all metropolitan Magistrates Courts – Adelaide, Christies Beach, Elizabeth and Port Adelaide, along with the Youth Court.

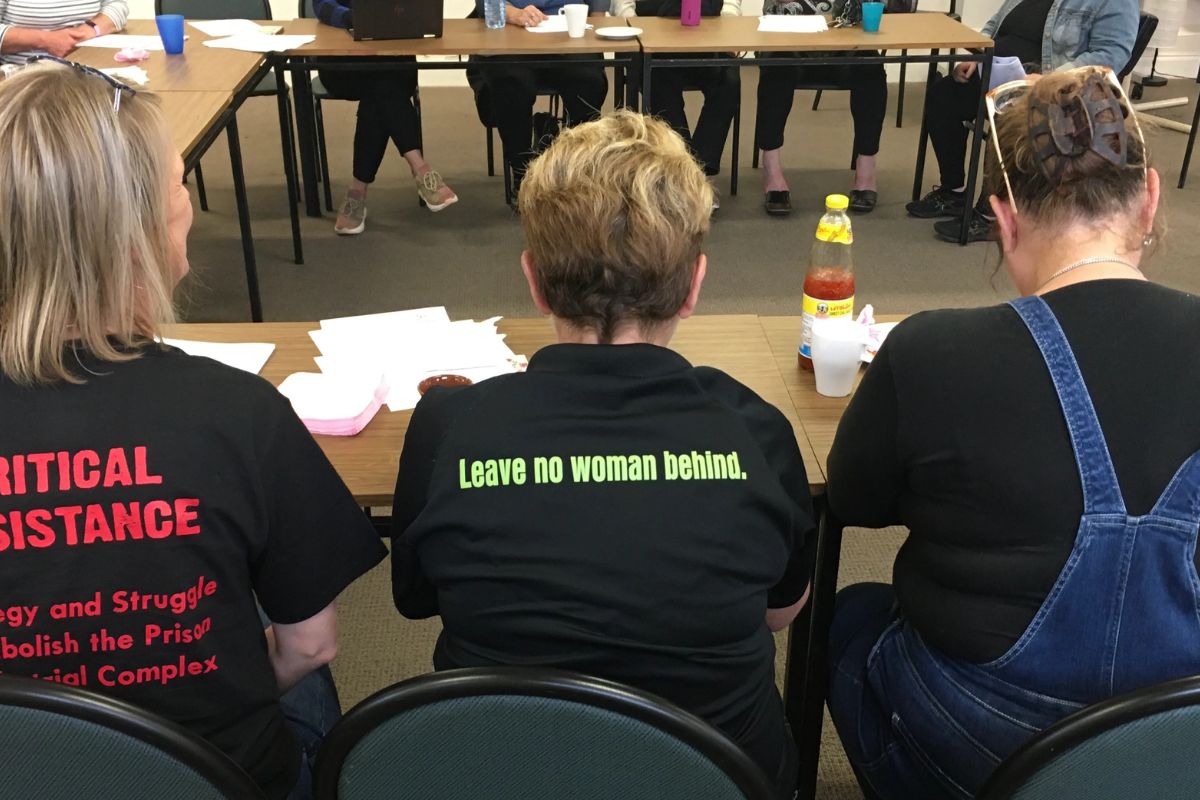

Linda Fisk has led Seeds of Affinity since 2006, a group supporting women that exit prison that is led by women with lived experiences of incarceration.

Fisk said there was a “large percentage” of drug and alcohol issues among the women the group supported.

“When you see yourself as a criminal drug addict, it’s very hard to imagine yourself doing anything different,” she said.

“The main part of the work for us is building that new identity and sense of self-belief that allows them to see themselves in a different way.”

SA has the lowest reoffending rate in the country, but still, a 2023-2024 report on government services showed about one in three convicted offenders return to prison within two years of their release.

Stay informed, daily

For many ex-prisoners, the post-release difficulties extend far beyond the drug counselling programs, with employment programs described as being difficult to navigate.

The WRRR is a government program that provides released prisoners employment opportunities as part of the state government’s plan to reduce recidivism rates by 20 per cent by 2026.

According to a Workskil report, the WRRR program had a 52 per cent successful employment rate among released participants.

Fisk warned there also was a “gaping hole” in the services offered to women after prison.

“A lot of women get pushed into labour jobs through the WRRR program and they might be fine for a few weeks, then there will be a collapse and the jobs lost — then we’re in a mode of crisis again.

“I believe very strongly that it’s not the right thing to do with women,” Fisk said.

Fisk, who was recently nominated alongside co-founder Anna Kemp for the 2026 Local Hero for SA at the Australian of the Year state awards, also wants to see the state government adopt the “holistic” approach to community transition similar to that of Seeds of Affinity.

Stable housing was the “number one” most important factor for women when transitioning back into the community, she said.

“They need supportive housing and they need access to social housing that’s sustainable and safe so they can make a place for themselves in the community.”

“I have women that get out and actually want to go back to prison because they’re living on the street. It’s really unsafe.”

A spokesperson for Emergency Service and Correctional Services Minister Rhiannon Pearce said the state government “funded a number of programs” to assist former detainees with drug and alcohol support, but would remain open to ideas from groups like Seeds of Affinity to further assist the rehabilitation of former prisoners.

“South Australia has the lowest recidivism rate in the nation and one key of the contributors to this success is programs such as Work Ready, Release Ready,” the spokesperson said.

“About 1500 former prisoners have received employment placements through the program, with more than 800 individuals obtaining ongoing work.”

The spokesperson said further work was happening around housing opportunities for prisoners.

“WorkPlace is a housing facility based at Cavan with wrap around support which has been specifically created for men leaving custody who were at risk of being homeless upon release from prison,” the spokesperson said.

“Work is also currently underway at the $36 million New Generation Catherine House project in Adelaide’s CBD that will see more South Australian women supported into crisis accommodation and recovery services.”

Fisk said she would “give away” any awards “just to see women doing well and not returning to prison”.

“It’s no place for women to live and I hope that we put ourselves out of business because there’s not enough women going to prison. That’s our goal.”