‘Harvest of loot’: the colonial legacies of South Australia’s Benin Bronzes

In an exclusive book extract, InReview editor Walter Marsh explores how a group of bronze sculptures behind glass at the South Australian Museum reveals a complex story of British imperialism, a South Australian governor, and the hidden slavery connections of an Adelaide Hills dynasty. Marsh’s book The Butterfly Thief is being launched in Adelaide tonight.

On 21 November 1898, a shipment arrived at Port Adelaide. Arranged inside two crates designated as ‘ethnographic specimens’ lay half-a-dozen items, including a carved ivory tusk, a royal’s head, and a staff topped with a bird of prophecy.

“The following specimens were taken in Benin City. W. Coast Africa by the British troops in Feb. 1897,” read an accompanying memo from W.D. Webster, the London antiquarian who sent the package months earlier, adding that the bronzes were believed to be around 400 years old.

Webster’s sales pitch carried a note of urgency: he had already sold around £3,000 worth of Benin pieces to a prestigious client list that included museums in Oxford, Berlin, Vienna, Dresden, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Canterbury, and it would be “impossible to get any later on”.

“I may say that there is nothing left in Benin — what they were unable to bring away was destroyed,” Webster added.

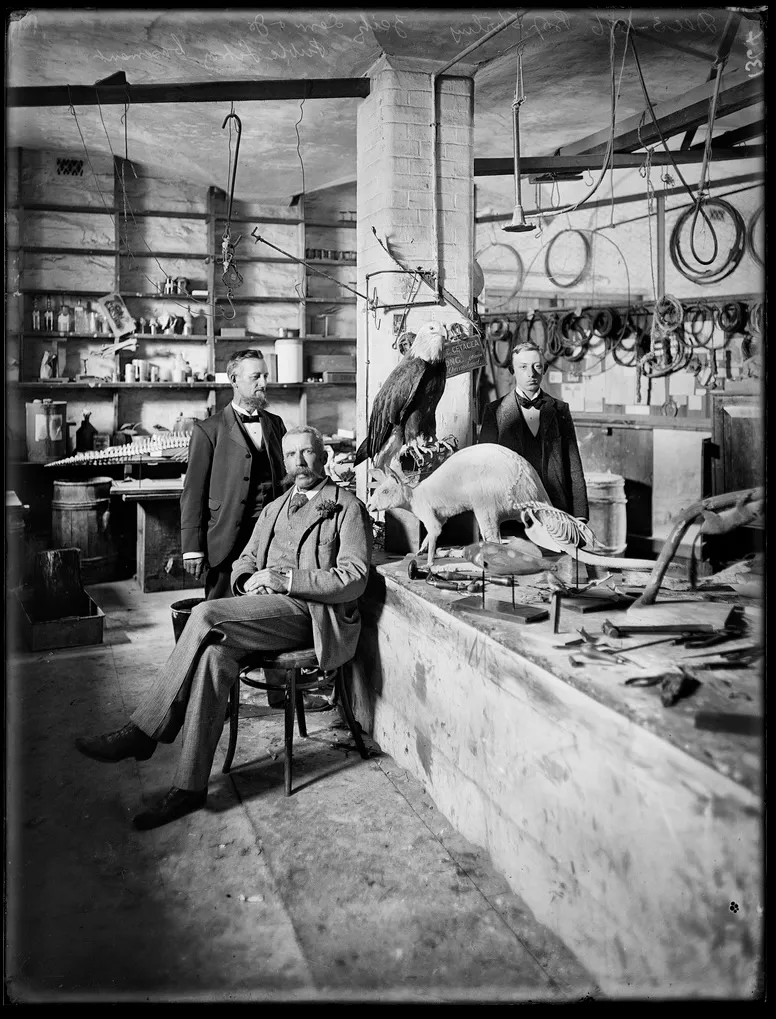

The shipment’s recipient was Dr Edward Charles Stirling, the then-director of the South Australian Museum. Since returning home to South Australia in 1881, the surgeon and zoologist casually known as ‘Ted’ had worked hard to elevate its ailing local museum to the kind of “European reputation” enjoyed by other institutions around Australia and New Zealand.

But there was a problem: the museum’s funds were “painfully low” — his staff could barely afford to print labels, let alone acquire sought-after treasures from around the empire. It was an embarrassing prospect, and in a letter to the editor of the South Australian Register, Stirling made a public plea for some private citizen to purchase the cargo and, Stirling hoped, donate it to the museum. The alternative, he suggested, would be a great loss:

"The passage from Mr Webster’s letter referring to the disposition of the Benin specimens that have passed through his hands once more excites a regret that has been so often felt — viz., that collections gathered in English countries and dependencies have so often been allowed to pass from the countries to which they belong."

When Stirling spoke of ‘countries’ and ‘belonging’, however, he didn’t mean the city of Benin, the capital of Edo State in present-day Nigeria, or its people — he was referring to the British Empire that now laid claim to the territory.

In recent years, Webster’s bronze treasures have sat behind glass in the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, positioned in a thoroughfare between a family changing room and a stairwell. In the year I worked at the South Australian Museum, I would regularly pass them in the hall, and reflect on their current state of physical and geopolitical limbo, as their counterparts at the British Museum and other overseas institutions became lightning rods in the growing conversation around western museums and their colonial legacies.

A few years ago, some of my former colleagues published part of Webster and Stirling’s correspondence on the website ‘Digital Benin’, part of an effort by an international dialogue group to build a transparent, searchable database that illustrated how one West African city-state’s riches were scattered to museums around the world. But this paper trail only seemed to scratch the surface.

You might like

Smiles and white umbrellas

I didn’t have to look far. Just a few years after their arrival in Adelaide, the story of how those bronze and ivory treasures left Benin was recounted in playfully lurid detail in July 1914 by South Australia’s 17th governor, Sir Henry Galway. In an era when gubernatorial posts served as an imperial clearing house and golden handshake for fusty retired admirals or well-connected aristocrats, Galway had quickly charmed the locals by exhibiting the “dash and courage of the soldier” and speaking with a refreshing “freedom and happiness”.

One July evening at Adelaide’s Public Library, just next door to the museum, Galway regaled an audience with the ‘thrilling exploits’ of his soldiering days, casting his mind back to a time before he gained a knighthood, married a baroness, changed his name from Gallwey to the more stately ‘Galway’, and played a key role in one of the British Empire’s bloodiest conquests.

Galway’s account of the 1897 invasion of Benin City was, by 1914, a well-rehearsed one-man show. Complete with “electric light illustrations”, Galway explained how, as deputy commissioner and consul of Britain’s Niger Coast Protectorate, he had sought to broker a free trade treaty with Ovọnramwẹn Nọgbaisi, the Oba of Benin and heir to a long, uninterrupted line of monarchs dating back to the 11th century.

With its strategic position along the Niger River and access to valuable commodities such as palm oil and rubber, Benin was prized as the European powers made their 19th-century ‘scramble for Africa’. For years, the British Royal Niger Company had hoped to monopolise what Galway called ‘one of the many blank spaces on the map known as Darkest Africa’:

"The potential possibilities of those territories, of which Nigeria is the richest and most extensive, are incalculable. The very prosperity of our trade at home creates a demand for more markets — which lie in tropical Africa — and these potential markets are our own, we may do as we please with them."

But, Galway said, it was “very patent we could not attempt to open up the country by means of smiles and white umbrellas”. He had travelled to Benin City himself in March 1892 to negotiate a treaty, where the Oba asked repeatedly if the document — that would grant Queen Victoria’s “gracious favour and protection” in return for unrestricted free trade across the Oba’s territories — meant “peace or war”. Through interpreters Galway assured him that this was a peaceful mission, and he would later claim that they came to an agreement. But even in Galway’s own account, there is little about the negotiations or the resulting document that sounds fair or binding — it was the captain himself who signed the treaty in the Oba’s name.

Clearly, the Oba did not consider Galway’s piece of paper to hold any legitimacy, and over the coming years he continued to control trade, and even placed religious bans on some of the goods most coveted by the British. Within months of the document’s signing, Galway and other British officials began plotting the Oba’s removal, perhaps via a ‘punitive expedition’, using his disregard for Galway’s dubious treaty as a legal pretext. In late 1896, James Phillips, a Cambridge-educated thirty-two-year-old serving as acting consul, wrote to the British prime minister complaining of the continuing obstacle that the Oba represented, and asked “permission to visit Benin City in February next, to depose and remove the King of Benin and to establish a native council in his place”.

Phillips never received a response, but in December 1896 he set out along the road from Gwato to Benin anyway. Phillips was resoundingly rebuffed, with the Oba’s emissaries warning him that their king was in isolation, and that the city was closed to outsiders during the sacred Igue festival. Any white man who attempted to enter, they told Phillips, would be killed — and on 4 January 1897, in a clash with the Oba’s men, that’s exactly what happened.

A ‘punitive’ expedition

Galway heard about the deaths of Phillips and five British officers a week later, and promptly wired the Foreign Office to approve a retaliatory attack on the city. Within less than a month the British had assembled a force of 1,200 men deployed from as far as Cape Town, Malta, and England, with enough arms and provisions to lay siege to the city. While the British would claim the Oba had forced their hand, the killing of Phillips provided a long-awaited cover story for a punitive exhibition that would achieve the very coup that Phillips had hoped for; like many 19th-century conquests, the justification of the Benin expedition relied on a selective reading of the timeline of colonial incursions and reprisals that recast a violent British invasion as a righteous act of self-defence. The remarkable speed with which a 1,200-strong invading force could be assembled was testament to just how well-oiled the British ‘punitive’ machine had become.

The British forces set out for Benin armed with the latest in European war technologies, including Maxim machine guns, rocket tubes, seven-pounder mountain guns, ‘gun cotton’ nitrocellulose explosives, bolt-action rifles, and millions of bullets. While British gunships approached the city from the river, Galway led a column of 500 men who retraced Phillips’ steps along the Gwato–Benin road, using their firepower to carve a path through to the city over five days of what Galway would describe as ‘merry bush fighting’.

A ‘regular holocaust’

Galway’s party arrived in Benin City on 18 February. Once inside, the captain — the only one of the invaders to have previously set foot in the city — led the way through to the Oba’s compound. The Oba had fled, but the sight of many dead, some of whom had apparently been sacrificed by the Oba’s priests to sway the outcome of the conflict, led the British troops to dub Benin the ‘City of Blood’. For colonisers such as Galway, the macabre practices of ‘fetish rule’ was a perfect example of the civilising imperative of the British Empire — even as his troops laid waste to the city.

Stay informed, daily

Later, in Adelaide, Governor Galway would claim “the enemy must have lost very heavily, but no reliable estimate can be given”, before adding that they buried “nearly 900” bodies in the aftermath. Soon after, Galway’s countrymen razed the houses of the Oba’s chiefs before a bigger blaze engulfed the entire compound. According to Galway, the city soon showed “evident signs of the white man’s rule: equity, justice, peace and security”. He also added, “the place was a regular holocaust — and very little was saved.”

What survived the fires soon left the country, with Galway noting ‘that hundreds of bronze plaques of unique designs; castings of wonderful detail; and a very large number of carved tusks of considerable age’ were soon discovered. Like other British visitors to the city, Galway had noticed such works during his earlier treaty-signing mission; in his November 1896 letter to the prime minister, even Phillips had flagged that ‘sufficient ivory may be found in the King’s house to pay the expenses in removing the King from his Stool’. Photographs of the aftermath show British troops posing for the camera surrounded by bronze plaques and bundles of seized ivory tusks.

Over in Adelaide, Stirling eventually managed to find a local benefactor for Webster’s wares, guaranteeing their eventual acquisition by his museum. Later, in 1902, its Benin collection would grow to include an ‘Ama’ — a bronze plaque depicting two collared chiefs and a priest bearing vessels aloft in their hands — donated by Stirling’s brother-in-law, a British newspaper magnate.

By 1899, stories had begun to circulate in the press that the ‘great beauty’ of the artworks had ‘puzzle[d]’ ethnologists, with one archaeologist at the British Museum publicly speculating that they were actually the work of “some European bronze founders who settled there in the 16th century”. Where Galway and his troops had used dubious legal documents and force to usurp Benin sovereignty over land and resources, the academics at the museum were now finishing the job by delegitimising Benin’s connection to its stolen cultural heritage as well.

A complicated legacy

Ted Stirling’s own place the thriving field of late-19th-century natural history, ethnology and race science — in addition to the Benin acquisitions, he would also drive the collection and study of the remains of First Nations Ancestors on a mass scale, displayed in his own museum and exchanged with institutions around the world — was further complicated by the fact that, in many ways, he personified the murky ties between respectable British society, the violent origins of its wealth and influence, and the complex hierarchies of race and class upon which it was built.

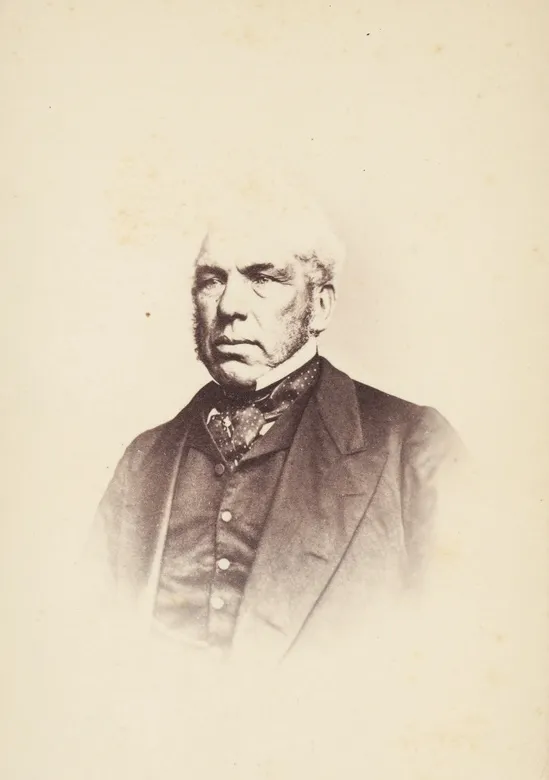

Recent research by Stirling’s descendant Beth Robertson has revealed that Ted’s father and family patriarch, Edward Stirling Sr, had been born into slavery in Jamaica — the illegitimate son of an unknown enslaved woman and Archibald Stirling, a Scot who had spent twenty-five years in the Caribbean managing his family’s plantations. When the British parliament abolished slavery in 1833, Archibald used part of the £12,500 he received in compensation for the family’s freed 690 slaves to send his son Edward to a far-off colony with £1,000, a good surname, and, it seems, a tacit understanding to stay well away from the legitimate, white branch of the family.

While a painted portrait held in the Art Gallery of South Australia depicts Edward Stirling Sr as a typical Victorian gentleman with greying hair and sideburns, a long, straight nose, and sunken cheeks that appear to be a pale shade of pink, contemporaneous photographs of Edward — and oral traditions that his son’s nickname around town was the racist slur, n***** — suggest there was no denying their mixed ancestry. On the one hand, the Stirlings’ success shows that in colonial South Australia, it was a kind of open secret that with enough money and connections you could hide in plain sight. But between the whitewashed portrait and Ted’s nickname, it seems they must have held no illusions about their unique and precarious place in the racial hierarchies of the British Empire.

Given the times he lived in, perhaps it’s no surprise that Ted Stirling leant into the persona of the Cambridge-educated gentleman scientist and doctor from venerable Scottish stock, even as his canny navigation of the elite worlds of academia, politics, medicine, and natural history museums saw him replicate many of the racial hierarchies that marked him, like his father, as ‘other’. But perhaps his enthusiastic conformity to the archetype of the gentleman naturalist, the collector, also speaks to its power: that was the kind of man who could open doors, command respect and acclaim — and collect pretty much anything he wanted.

Stirling had retired from the directorship by May 1914, when a newspaper report of Galway’s first tour of the museum’s galleries noted that the new governor was “naturally particularly interested in some exhibits from North-West Africa“. Galway’s support of the South Australian Museum throughout his term as governor would be recognised with the naming of a species of fish in his honour, and in December 1915, Galway presided over the grand opening of the museum’s new east wing — the same freestone giant that today houses its Benin pieces.

At the east wing’s grand opening in late 1915, Galway spoke of the important role that museums played for the nation and the empire:

"The greatness of the nation must be measured not alone by its wealth and apparent power, but by the degree in which its people have learned together in the great world of books of art and of nature and of pure and ennobling joys."

For all their grandiose language, such statements obscured the deeper role of the colonial museum: as places for Britain and other European powers to launder their reputations and their ‘collected’ spoils as they set about the dirty, extractive work of empire-building.

Today, the bronzes that Galway helped seize, and Stirling later acquired, remain in situ until they join the growing numbers of bronzes being repatriated from museums around the world. For now, new interpretive panels acknowledge the “tendrils of the British Empire”, and the “difficult legacy” that demanded natural history museums become “active voice in the growing conversations around their return”. Such rhetoric would be hard to imagine half a century ago, but even these signs of progress can only tell a fraction of the story.

Perhaps Governor Galway himself had put it more succinctly at the Public Library back in 1914: it was a “regular harvest of loot.”

This is an edited extract from The Butterfly Thief: adventure, empire, and Australia’s greatest museum heist (Scribe, September 2023) by Walter Marsh