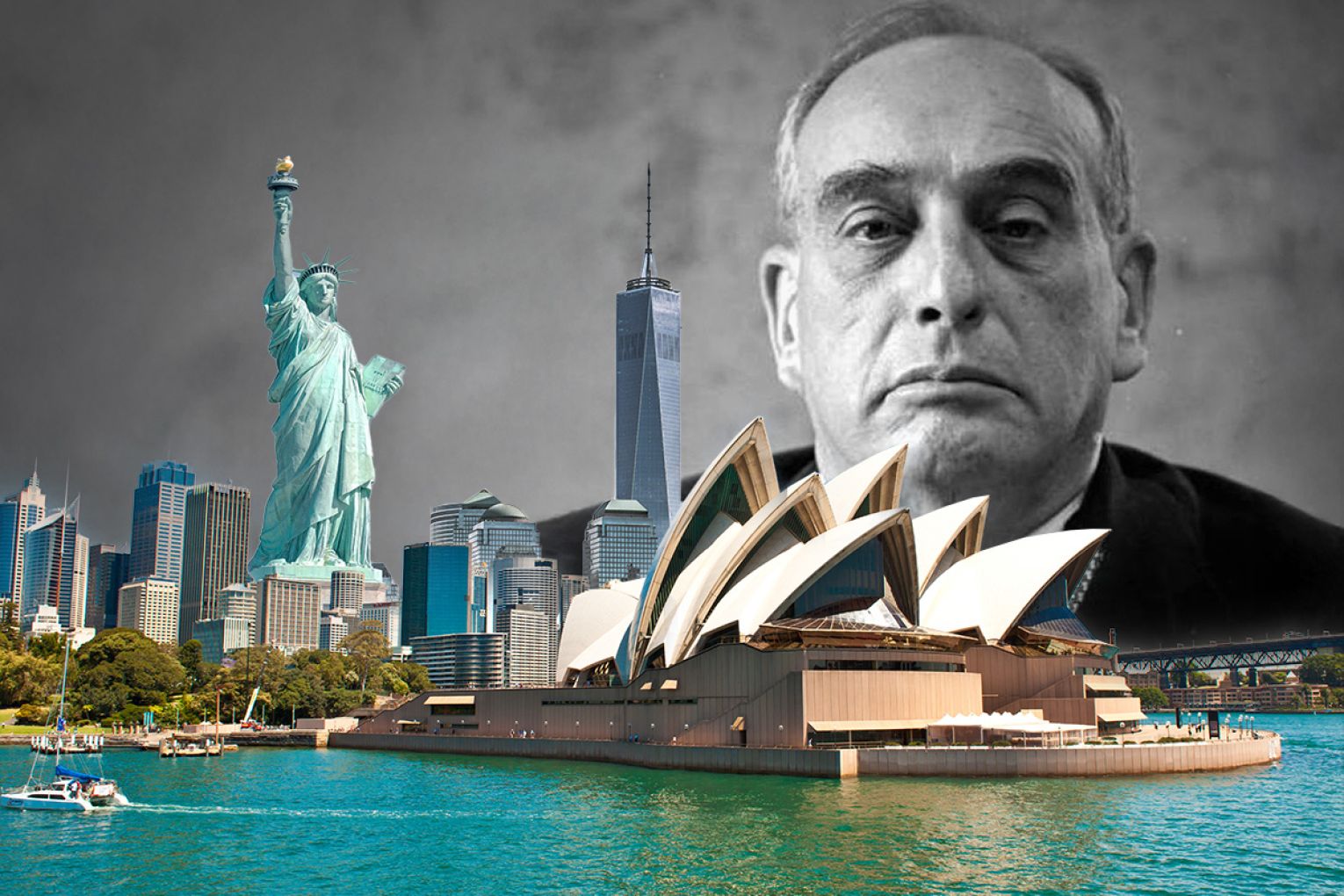

The Stats Guy: Australia’s lessons from New York’s past

Australia is entering a generational infrastructure build-out, this tale of New York’s past offers important lessons for today.

One of my great intellectual joys is reading biographies.

I am currently working my way through Pulitzer Prize-winning works. The last one I finished was published 50 years ago and is brimming with lessons about modern day infrastructure and urban planning.

The biography was about Robert Moses, the unelected master builder who reshaped New York in the first half of the 20th century.

Moses was a controversial figure, using an unrivalled combination of political cunning, legislative manipulation and institutional power to construct the city’s parks, highways, bridges, beaches and tunnels.

Although he never won an election, he wielded more influence over America’s largest metropolis than any mayor or governor of his era.

To this day, large parts of New York City (and New York state) act as the legacy of this idealist who turned into a power-hungry egomaniac and ran a parallel government of sorts.

Robert Caro’s biography of Moses, The Power Broker, is widely regarded as one of the greatest biographies written because it is both a monumental feat of investigative reporting and a gripping study of power itself.

Caro spent seven years unearthing documents, interviewing hundreds of sources and dissecting the machinery of urban politics.

The result is a 1344-page (or 66-hour audiobook) masterpiece that reads like a political thriller yet also serves as a profound lesson in how democratic systems can be bent by a determined individual.

We, as a modern audience, can learn many lessons regarding today’s infrastructure.

How to stop a modern-day Robert Moses: Lessons for building better, fairer infrastructure

If you want a quick introduction to Moses and aren’t keen on a behemoth of a book before reading this column, maybe this short biography on YouTube will help.

Moses built more roads, bridges, parks and tunnels than any individual in American history. Yet he also bulldozed neighbourhoods, entrenched (racial) inequality and locked New York into insane car dependence for generations.

The brilliance of The Power Broker lies not just in recounting Moses’ achievements, but in revealing the methods that allowed one unelected official to shape a metropolis in ways that often ran counter to the public interest.

I am claiming those methods hold powerful lessons for today’s policymakers.

If we want infrastructure that serves the public at the best price, we must understand how Moses built against the system and how the system allowed him to do it.

1. Beware the unsupervised authority

Moses’ greatest weapon was the public authority. These organisational constructs were entities insulated from political oversight, funded by their own revenue streams and governed by legislation he wrote himself.

These authorities could issue debt, buy land and start construction without transparent scrutiny. A public authority earned money by collecting tolls on bridges and roads and was free to spend it.

Lesson for today:

We must strengthen oversight of infrastructure authorities rather than weaken it.

You might like

- Independent boards must be genuinely independent

- Vast revenue streams and spending shouldn’t occur without parliamentary review

- Major decisions require line-of-sight from the public, not just from a minister’s office.

The entities building our infrastructure should be hyper-transparent.

2. Cost transparency is key

One of Moses’ signature moves was the strategic underestimate.

He would pitch a project at an attractive price, get the go-ahead, start construction immediately, then return to politicians with requests for ever more money as costs predictably escalated.

Politicians almost always paid. They couldn’t be seen in the public’s eye to cancel a project after they invested so much money into it already.

Readers of popular psychology books will understand just how powerful the sunk-cost effect can be.

Lesson for today:

Mandate independent cost estimates at multiple stages and publish them.

- Contingency assumptions must be visible

- Revised budgets must trigger automatic reviews

- Any accelerated start should be accompanied by a stop button if costs blow out

Infrastructure mega projects naturally involve uncertainty, and costs can escalate for legitimate reasons (global supply chain shortages, natural events and the like), but financial transparency is the bare minimum taxpayers should demand.

3. Make route and land-acquisition decisions transparent

Moses often routed highways through the neighbourhoods that would resist least (typically poor, minority, or politically marginal areas) while protecting wealthy districts with political clout.

Lesson for today:

We must demand a transparent, data-driven justification for route and site selection.

- Social-impact assessments aren’t optional

- Require community consultation early enough to matter

- Include long-term equity outcomes, not just travel-time models

Infrastructure defines a city’s social geography for generations. It cannot be decided in back rooms.

4. Don’t fall for the “fait accompli” narrative

Caro documents Moses’ mastery of urgency.

He would create artificial deadlines, start small parts of a project, or launch bulldozers before funding was secured. Politicians then had no choice but to continue.

Lesson for today:

Governments should treat premature construction as a red flag.

- No project should break ground without full funding approval

- No land acquisition should occur before statutory reviews are completed

- Any early works strategy must have a transparent rationale and cap

Momentum is useful in politics. But in infrastructure, unchecked momentum leads to bad projects becoming inevitable ones.

5. Strengthen procurement integrity and reduce patronage risks

Moses used a system of favours, loyalty networks, and preferential treatment of contractors to secure political and bureaucratic support.

While outright corruption was rare, structural bias was widespread.

Lesson for today:

Stay informed, daily

Procurement processes must be defensible from both corruption and political pressure.

- Publish shortlists and justification

- Create a system allowing for genuinely competitive tendering

- Track contractor performance transparently

- Rotate leadership within authorities to prevent power fiefdoms

Big infrastructure attracts big interests. Guardrails matter.

6. Governance over charisma

Moses was a master storyteller, a builder-hero who played the press brilliantly (for decades he wasn’t criticised publicly).

The spectacle of construction, the ribbon-cuttings, the drama, his aura turned him into a political force despite not being an elected official.

Lesson for today:

We must separate public-relations theatre from evidence-based decision making.

- Release business cases in full

- Require agencies to publish post-completion evaluations

- Create incentives for politicians to champion maintenance and upgrades, not only shiny new projects

The measure of an infrastructure system is not how much concrete is poured but how well the network performs.

7. Build capacity to push back

Caro makes clear that Moses’ rise was enabled not only by his genius, but by the weakness of the democratic institutions meant to check him.

Legislators didn’t read the bills. Governors were too busy. Mayors lacked expertise. Civil society lacked data.

Lesson for today:

Healthy infrastructure governance requires a strong democracy.

- Parliaments need real infrastructure literacy and real subject matter experts in house

- Communities need access to accessible, high-quality information

- Researchers and journalists must be equipped to scrutinise project economics

- Opposition parties must treat infrastructure as policy not as ammunition

A system that cannot say “no” will eventually be captured by those who want to say “yes” to the wrong things.

8. Plan for people

Many of Moses’ projects reflected a singular worldview: The primacy of the automobile. Parks, beaches, and recreation existed, but almost everything was ultimately optimised for cars. The long-term consequences for urban form were immense.

Lesson for today:

Infrastructure must reflect the society we want, not the assumptions of a single era.

- Integrate housing, land use, and transport planning

- Model emissions, equity, access, and resilience

- Plan for ageing populations, changing work patterns, and emerging technologies – take demographic certainties into account early

Infrastructure is destiny and we must choose our destiny intentionally.

The Moses warning

Moses was not a cartoon villain. He was an exceptionally talented builder operating in a governance system he built himself and that rewarded speed over transparency and spectacle over accountability.

His achievements were real, but so were the costs.

The lesson of The Power Broker is that infrastructure can be shaped by individuals who are not elected, not accountable, and not guided by long-term public interest. We must build institutions strong enough to attract the most talented builders while at the same time resisting to hand over too many powers.

Australia is entering a generational infrastructure build-out (nowhere more than in Queensland as Brisbane prepares to host the 2032 Olympics).

The stakes are enormous. The question Caro invites us to ask is simple: Are we building the safeguards as fast as we are building the projects?

Regular readers of this column might have been reminded of my previous column about the need to depoliticise infrastructure in Australia and my column arguing Australia is only a rich country because we have strong institutions.

The systems on which this country was built matter and must constantly be strengthened and evaluated. If you work in the infrastructure, housing, or political space, The Power Broker would be the ideal summer read.

Simon Kuestenmacher is a co-founder of The Demographics Group. His columns, media commentary and public speaking focus on current socio-demographic trends and how these impact Australia. His podcast, Demographics Decoded, explores the world through the demographic lens. Follow Simon on Twitter (X), Facebook, or LinkedIn.