Photographing Asia

In an instructional series, photographer Alex Frayne gives CityMag a lesson in travel photography, including advice on how to frame a country’s history in its present and what to pack.

“If you look at everything straight on, there is nothing to be afraid of…” Akira Kurosawa

The mistake artists sometimes make when approaching another culture is to believe that during say, a four week stint, they might fully comprehend and understand the nature of that culture. Try four years, and you might just scratch the surface. But in a small window of time one risks seeming like those idiots utiles of the 20th century, the Western intellectuals who were invited to Communist countries and driven around by party officials for a few days before declaring in their press dispatches that “the peasants are happy and the revolution is proceeding as planned.”

A better approach for photographers is to eschew naive tourist notions of “what is a place like?” and instead to think like an artist.

“How do I respond to and interrogate this vastly different culture? The keyword here is “respond ”, as it throws the onus onto you to be active and assertive rather than passive and reactive. How do you imbue your images with an imprint that is yours?

Photographers have at their fingertips an arsenal of tools to achieve this – lens choice, format choice, the ‘crop’ and the decisions around colour versus monochrome. But perhaps the most powerful tool at your disposal is your own preconceived notions of a culture that are derived from all the Arts – film, literature, visual arts and so on.

These notions can be reinforced or subtly subverted in your own responses to a culture; and in the best cases can lead you to new and exciting revelations of self.

For me, travelling to Tokyo a few years ago meant going into the country of the revered film maker Yasujiro Ozu. His classic films Late Spring (1949), Tokyo Story (1953) and An Autumn Afternoon (1962) are now seen as landmark works of Asian Cinema. His much-heralded use of the “Tatami Shot” was all I needed to provoke me into travelling to Japan; and I intended to see every frame from the Tatami height, using Ozu’s preferred lens, the standard 50mm.

The “Tatami shot” is photographed from the height that results from kneeling on an imaginary tatami mat and then framing an image. It puts you roughly level with a person’s sternum – radically different to the traditional western approach which is to be standing level with the subject’s eyes. It forced me to view the Japanese world very differently. Ozu’s world was inhabited by stories of families and relationships.

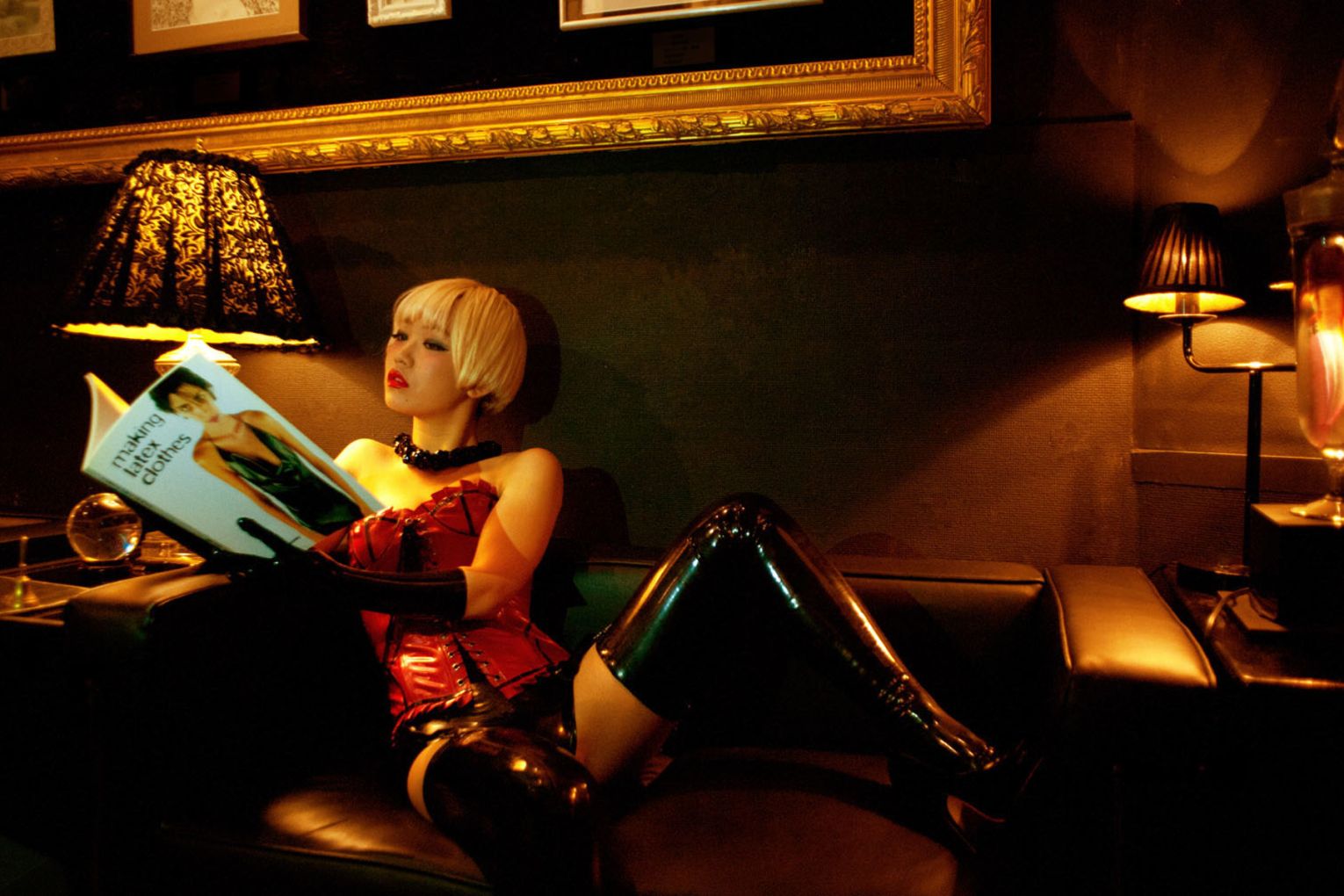

I wasn’t in the business of creating homages to Ozu, nevertheless, the Tatami framing was immensely useful as I made my way through Tokyo shooting all manner of people and places, including the Bondage Queen herself, pictured above.

She is quite well-known in the city and entertains people at a club in Rippongi. In this way she funds her college studies. Who knew? Not me.

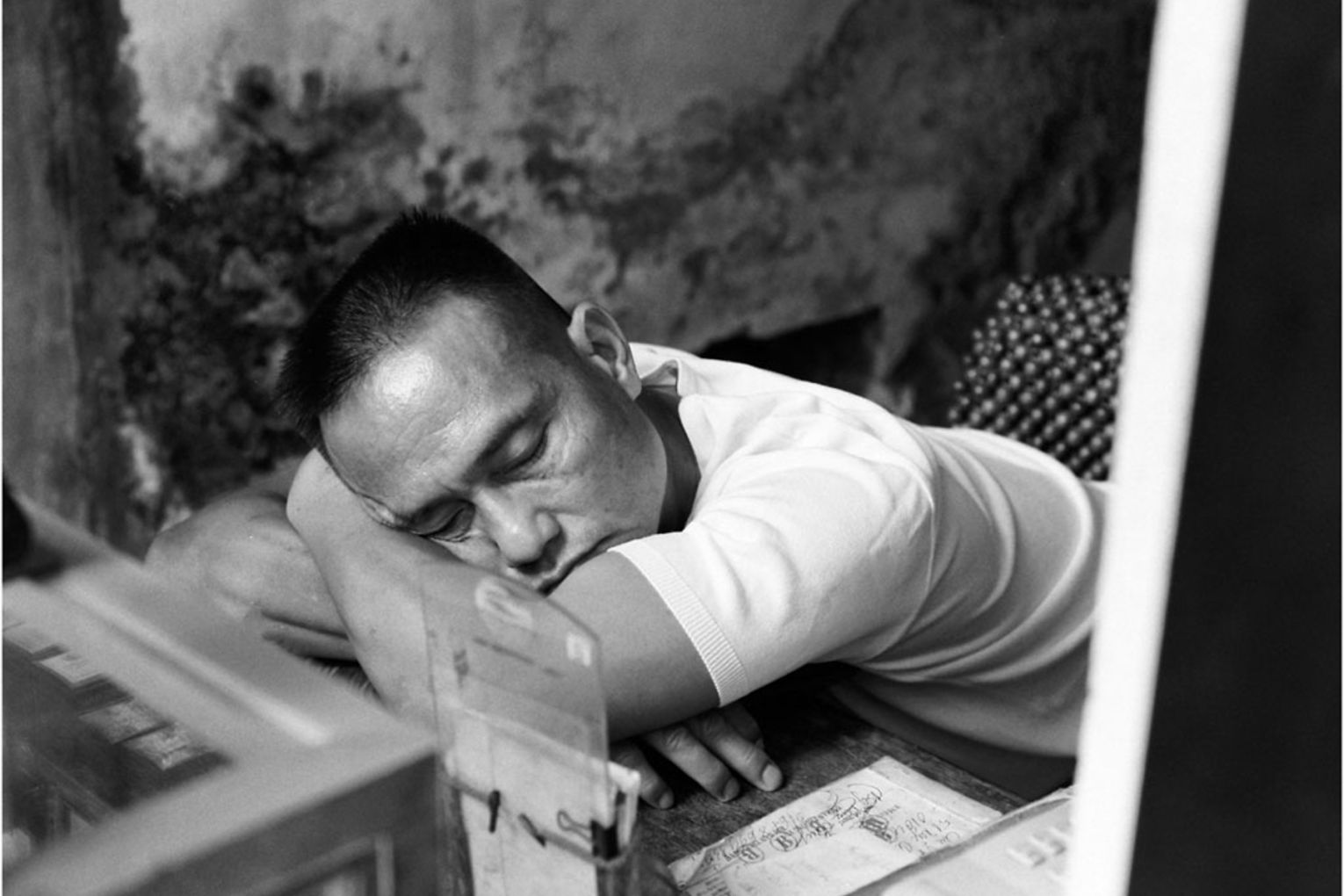

In South Korea, my “way in” to this fascinating culture was through newsreel footage I saw years ago that covered the war that ravaged the peninsula in the 1950s.

I decided I would shoot only in black and white and seek out military perspectives of a country still formally at war with the North.

Adopting this disposition enabled me to see the truth of a country that lives perpetually on the precipice of conflict and, of course, The Big One, The Bomb.

In Vietnam, I saw the faces and places of a country that had been through a war in my lifetime (I was about to be born when the Vietcong stormed Saigon).

I asked myself – can I see on these faces the indelible mark of war and horror? Certainly, among the upwardly mobile younger classes I could not – but eventually, slowly, the unforgettable spectre of that time emerges in a place like Hanoi.

The great question of Vietnam, the same one ruminated on by politicians, artists and thinkers is “how did this people take on the biggest and most powerful military machine in history, and win!? If you look hard through your viewfinder, you may find an answer.

Travel practically

When planning a trip with photography as your form of expression, be careful of heeding advice to ‘travel light.’

Sure, be practical with packing; but I’ve always thought you should bring whatever camera gear will help achieve your goals.

It is somewhat illogical to prioritise convenience over artistic integrity. If levity is your goal though, the range of compact cameras with large sensors and great lenses is growing almost monthly, led by Fuji, Ricoh and Panasonic. Indeed the latter now has a tiny compact camera with a full frame sensor! (s9 model).

If you’re like me, shooting primarily film, you’ll find labs and film developing spots all through Asia. I recommend travelling sans tripod. Every time I travel, I do pack a small tripod. And every time I return home I’m reminded how little I used the thing.

Local knowledge is the key to the holy grail of ‘access’ and as a general rule of thumb I spend 50 per cent as much time organising contacts for my destination as I do staying in the actual country itself. A local contact can also act as a translator for situations that require the nuances of language. This person will offer you personal advice about topics and people that is absolutely invaluable.

The last piece of advice is perhaps the most important.

When shooting overseas in the non-Anglosphere make sure you do everything very, very slowly. Do not demand anything of anyone. Do not talk at people. Walk slowly and calmly. Do not roll your eyes or huff and puff when things don’t go your way.

Do not whinge because your soy latte isn’t quite the way you like it. If you habitually tut-tut and compare your host city to cozy little Adelaide, you will quickly find out about what it feels like to be “Othered” in a foreign land.

I have seen this happen and it isn’t pretty. Just because you are a hero on Facebook when it comes to world politics, tariffs and solving the crisis in the Middle East, it does not mean this ‘knowledge’ will translate into making good photographs.

And be careful, but not irritatingly so.

As Ernest Hemmingway once said, “The best way to find out if you can trust someone, is to trust them.”